Wikipedia isn’t just a bunch of volunteers typing away in their basements. Behind the scenes, some of the world’s most respected cultural institutions are quietly helping shape what you read online. GLAM-Wiki partnerships-short for Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums working with Wikipedia-are turning public knowledge into something more accurate, more inclusive, and more accessible than ever before.

What Exactly Is a GLAM-Wiki Partnership?

It’s a simple idea: institutions that hold vast collections of artifacts, documents, photos, and historical records team up with Wikipedia editors to put that knowledge online. These aren’t just photo uploads. They’re full collaborations-training staff to edit Wikipedia, releasing underused archives under open licenses, hosting edit-a-thons, and even co-writing articles with curators who know the material better than anyone.

Before 2020, most GLAM-Wiki work happened in fits and starts. Now, it’s institutionalized. Major museums like the Smithsonian, the British Library, and the Rijksmuseum have dedicated staff whose only job is to manage Wikipedia partnerships. They don’t just hand over files-they build long-term relationships with editors, create internal policies for open access, and track how their contributions improve public understanding of history and culture.

Recent Wins: What’s Changed in 2024 and 2025

In 2024, the National Archives of Canada launched a program to digitize and release 50,000 historical photographs under a Creative Commons license, specifically for use on Wikipedia. Within six months, those images appeared in over 1,200 articles-many of them about Indigenous communities, women in early Canadian labor movements, and forgotten wartime efforts. For the first time, these stories were no longer buried in physical archives but visible to anyone with an internet connection.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York didn’t just upload high-res images of its collection. They trained 80 of their curators and educators to edit Wikipedia. The result? Articles on lesser-known artists like Alma Thomas and Käthe Kollwitz were expanded with academic citations, provenance details, and exhibition histories that had never been public before. These weren’t just edits-they were corrections. Old, outdated entries about women artists were rewritten with proper context, not just added as footnotes.

In Australia, the State Library of New South Wales partnered with local Indigenous communities to co-create Wikipedia content about Aboriginal languages and cultural practices. Instead of outsiders writing about these topics, community elders and language keepers were invited to lead edit-a-thons. Articles on endangered languages like Wiradjuri and Yolŋu Matha now include audio pronunciations, oral histories, and traditional spellings verified by native speakers. This isn’t just about adding facts-it’s about restoring authority to communities who’ve been excluded from mainstream historical records.

Why This Matters Beyond Pretty Pictures

Wikipedia is the fifth most visited website in the world. For many people, it’s the first-and sometimes only-source they use to learn about history, art, or science. If Wikipedia’s content is biased, incomplete, or outdated, the damage ripples across education, media, and public policy.

GLAM institutions have the power to fix that. They hold primary sources: original letters, photographs, maps, diaries, and artifacts that can’t be found anywhere else. When these are properly licensed and integrated into Wikipedia, they don’t just make articles look better-they make them more trustworthy.

Take the case of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. In 2023, they released over 20,000 digitized objects from their collections, including 19th-century sewing machines, Civil War uniforms, and early computing devices. Editors used these to update articles on industrial history, women’s labor, and technological innovation. One article on the history of the sewing machine went from 300 words to over 2,500, with citations from original patent documents and factory worker interviews. That’s not just an edit-it’s a scholarly upgrade.

How It Works: From Archives to Articles

It’s not magic. There’s a clear process:

- Identify underused materials-photos, documents, or artifacts that aren’t on display or poorly documented online.

- Apply open licenses-most GLAMs now use CC0 or CC BY-SA so content can be freely reused.

- Train staff and volunteers-edit-a-thons, workshops, and online tutorials help curators learn how to write for Wikipedia’s style.

- Connect content to articles-editors match images and documents to existing Wikipedia pages that need them.

- Track impact-they measure how many views, edits, and citations result from each upload.

Some institutions even use AI tools to suggest which articles need images or citations based on gaps in content. The British Library, for example, used machine learning to identify 300 historical maps that had never been linked to Wikipedia. Within a year, those maps appeared in articles on colonial history, trade routes, and urban development-filling gaps that had gone unnoticed for decades.

Challenges and Missteps

It’s not all smooth sailing. Some GLAM institutions still worry about copyright, loss of control, or misinformation. A few tried to upload content without proper licensing, only to have it removed by Wikipedia volunteers. Others trained staff but didn’t follow up-resulting in one-off events with no long-term impact.

There’s also the issue of representation. Many institutions still focus on European art and Western history. The push now is to prioritize underrepresented voices: Indigenous cultures, African diasporas, LGBTQ+ histories, and non-Western scientific traditions. The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston recently partnered with Haitian scholars to rewrite articles on Afro-Caribbean art, correcting decades of colonial framing that labeled these works as “primitive” or “folk art.”

Another hurdle? Time. Curators aren’t editors. Writing for Wikipedia requires a different tone-clear, neutral, and concise. Many institutions now hire part-time Wikipedia liaison officers to bridge that gap.

The Bigger Picture: Knowledge as a Public Good

These partnerships are changing how we think about knowledge. For centuries, museums and archives kept their collections behind glass, locked in catalogs, or buried in dusty files. Access was limited to researchers, students, or the wealthy.

Now, knowledge is being treated like infrastructure-something everyone should be able to use, remix, and build upon. GLAM-Wiki collaborations are making that real. They’re turning static collections into living, evolving resources. A photo of a 1920s textile pattern isn’t just a picture anymore-it’s part of a global conversation about design, labor, and gender.

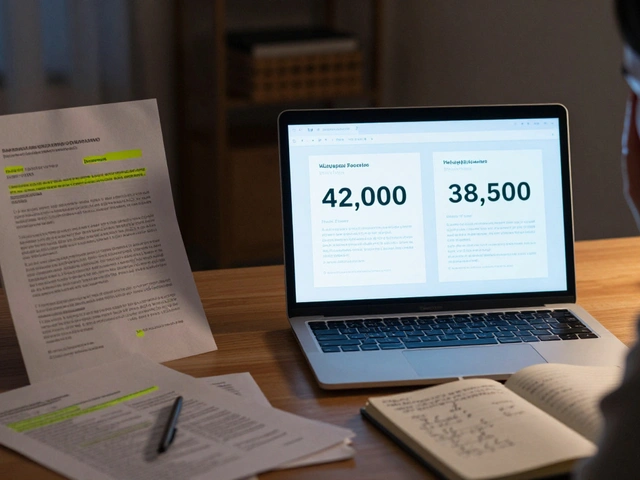

And it’s working. A 2025 study by the University of Oxford found that articles supported by GLAM-Wiki partnerships received 47% more views and 62% more citations than similar articles without institutional backing. More importantly, they were rated as more reliable by independent fact-checkers.

What’s Next?

The next frontier? Integrating GLAM content directly into Wikipedia’s AI-powered summary tools. The Wikimedia Foundation is testing a system where Wikipedia’s “Overview” boxes-those short summaries that appear at the top of search results-pull in verified images and facts from partner institutions. Imagine searching for “Taj Mahal” and seeing an authentic 1880s photograph from the British Library, labeled and sourced right in the summary.

Smaller institutions are catching on too. Local historical societies in rural Wisconsin, public libraries in Ohio, and regional art centers in Louisiana are starting their own small-scale partnerships. You don’t need a million-dollar budget. All you need is one curator, one open license, and one editor willing to help.

The message is clear: knowledge doesn’t belong in vaults. It belongs out in the open, where people can find it, use it, and make it better.

What does GLAM stand for in GLAM-Wiki partnerships?

GLAM stands for Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums. These are cultural institutions that hold historical, artistic, or scholarly collections. In GLAM-Wiki partnerships, they work with Wikipedia editors to share their materials openly online, improving the accuracy and depth of Wikipedia’s content.

Can anyone participate in a GLAM-Wiki edit-a-thon?

Yes. Most edit-a-thons are open to the public-whether you’re a student, a historian, a librarian, or just someone who likes to read Wikipedia. Institutions often provide training, source materials, and mentors to help newcomers get started. No prior editing experience is required.

Do GLAM institutions make money from these partnerships?

No. GLAM-Wiki partnerships are not commercial. Institutions release content under open licenses like Creative Commons, which means anyone can use it for free. The goal isn’t profit-it’s public access, education, and correcting historical gaps in knowledge. Some institutions receive grants to support these efforts, but they don’t charge for content.

How do I find out if my local museum or library has a Wikipedia partnership?

Check the institution’s website for a section on “Digital Initiatives,” “Open Access,” or “Community Engagement.” Many list their Wikipedia collaborations there. You can also search Wikipedia for “GLAM-Wiki” and your city or region. Local edit-a-thons are often advertised through public libraries or university libraries.

Why should I care if a museum uploads photos to Wikipedia?

Because Wikipedia is where millions of people go to learn. If a museum’s collection stays locked away, only a few experts ever see it. When those images and documents appear on Wikipedia, they become part of global education. A student in Kenya, a teacher in Brazil, or a researcher in Finland can all use them for free. It’s not just about visibility-it’s about equity in knowledge.