Wikipedia isn’t just a place to check facts-it’s one of the most powerful teaching tools in academic libraries today. Librarians across the U.S. are using it not to avoid criticism, but to turn it into a classroom. They don’t tell students to avoid Wikipedia. They teach them how to use it-smartly, critically, and confidently.

Why Wikipedia Belongs in the Classroom

Most students still get told to steer clear of Wikipedia in research papers. But that advice doesn’t match reality. Over 1.5 billion people visit Wikipedia every month. It’s the first stop for 87% of college students looking up a topic, according to a 2024 study by the Pew Research Center. Trying to ban it is like banning Google. The real question isn’t whether students use it-it’s whether they know how to use it well.

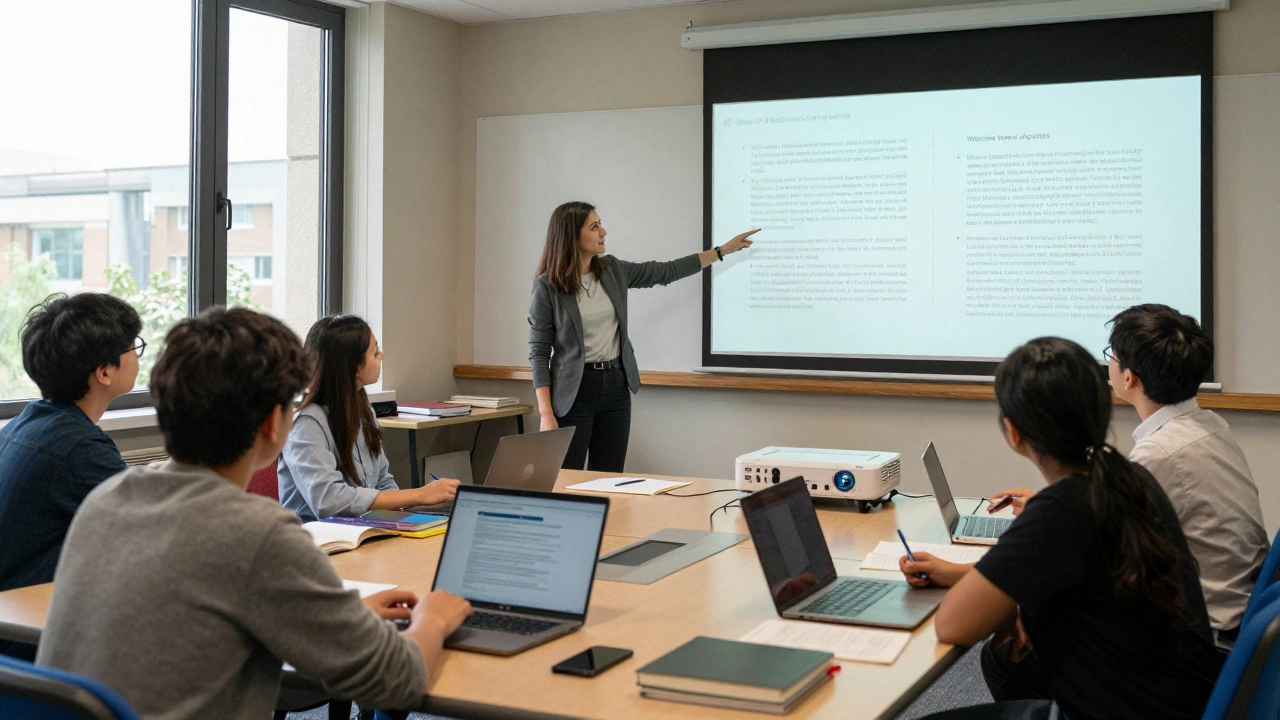

Librarians have shifted from fighting Wikipedia to teaching with it. In classrooms at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Ohio State, and the University of Michigan, librarians now run 45-minute sessions where students compare Wikipedia articles with peer-reviewed sources. They don’t just say, "This is wrong." They ask, "Why is this different? Who wrote this? What’s missing?"

The Five Skills Librarians Teach Using Wikipedia

Wikipedia isn’t taught as a source. It’s taught as a process. Here’s what students actually learn:

- Tracking citations - Students click on footnotes and trace claims back to original studies. One student found a Wikipedia claim about climate change was backed by a 1998 paper from the National Academy of Sciences. They learned to follow the trail, not just accept the summary.

- Reading the talk page - Every Wikipedia article has a "Talk" tab. That’s where editors argue over wording, accuracy, and bias. Librarians show students how to spot edit wars, repeated vandalism, or consensus-building. A 2023 project at the University of Texas found students who checked talk pages were 60% more likely to spot misleading edits.

- Identifying gaps - Wikipedia reflects who edits it. Less than 15% of editors are women, and most are from North America and Europe. Librarians ask students: "What topics are missing? Whose voices aren’t here?" Students then research underrepresented histories and contribute to Wikipedia themselves.

- Comparing versions - Using Wikipedia’s history tab, students see how articles change over time. One article on "colonialism" had its tone shift from neutral to critical after a group of graduate students added citations from postcolonial scholars. Students learn that knowledge isn’t static-it’s built.

- Understanding reliability scales - Wikipedia has a rating system: Stub, Start, C, B, GA (Good Article), FA (Featured Article). Librarians teach students to look for these labels. A Featured Article has gone through peer review by other editors. It’s not perfect, but it’s the closest thing Wikipedia has to peer-reviewed.

Real Classroom Example: The "Wikipedia Edit-a-Thon"

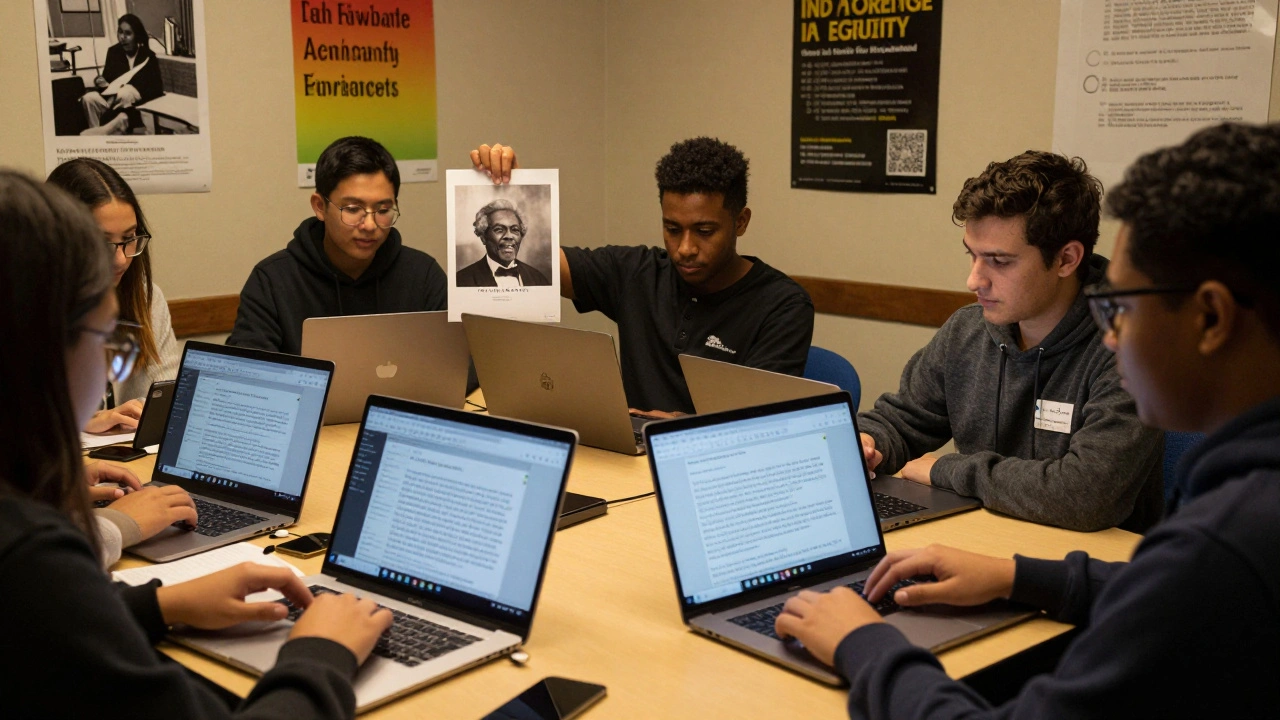

At the University of Minnesota, a librarian partnered with a history professor to run a semester-long project. Students picked underrepresented topics-like women in early African American journalism-and wrote Wikipedia articles from scratch. They had to find credible sources, cite them properly, and defend their edits on the article’s talk page.

One student wrote about Ida B. Wells an African American journalist and anti-lynching activist who founded one of the first Black-owned newspapers in the U.S.. Her original Wikipedia page was two paragraphs long. After 12 weeks of research, she expanded it to over 3,000 words, added 47 citations, and included photos from the Library of Congress. Her article was later tagged as a "Good Article."

That student didn’t just write a paper. She became a contributor to public knowledge. And she learned more about source evaluation than she ever did from a textbook.

Why This Works Better Than Traditional Research Guides

Traditional research instruction often says: "Use databases. Avoid websites." But students don’t live in libraries. They live online. When librarians teach them to distrust everything on the internet, they create confusion-not confidence.

Wikipedia gives students a real-world sandbox. They see how information is made, challenged, and improved. They learn that authority isn’t just about who published it-it’s about how well it’s supported, how transparent the process is, and how open it is to correction.

A 2025 survey of 1,200 undergraduates at 15 U.S. universities found that students who took Wikipedia-based information literacy workshops were 42% more likely to correctly identify a biased source and 37% more likely to cite sources properly in their papers. They didn’t just learn to avoid bad sources-they learned how to build better ones.

What Librarians Don’t Do

Good librarians don’t say Wikipedia is perfect. They don’t say it’s the best source. They say: "It’s a starting point-and a mirror."

They don’t teach students to copy Wikipedia. They teach them to reverse-engineer it. To ask: Who wrote this? Why? What’s not here? What evidence backs it up? That’s information literacy-not memorizing a list of "good" databases.

And they don’t expect students to become editors overnight. But they do expect students to understand how knowledge is made-and who gets to make it.

The Bigger Picture: Knowledge Equity

Wikipedia is a global project. But it’s not equally global. The English version has over 6.5 million articles. The Swahili version has about 100,000. The Quechua version? Less than 5,000.

Librarians are starting to use Wikipedia to teach not just research skills, but social responsibility. When students edit articles about their own communities-Indigenous histories, local immigrant stories, regional dialects-they’re not just learning to cite sources. They’re helping fix a broken system.

At the University of California, Berkeley, a librarian runs a workshop called "Decolonizing Wikipedia." Students research and write about Native American scientists, Latin American feminist movements, and Southeast Asian environmental activists. These aren’t just assignments. They’re acts of digital justice.

What Comes Next?

Wikipedia isn’t going away. Neither are students. The question isn’t whether libraries should engage with it-it’s how deeply they’ll go.

More libraries are now offering certification programs in Wikipedia editing. Some offer credit-bearing courses. The Wikimedia Foundation partners with over 400 U.S. colleges. And librarians are the ones leading the charge.

The future of information literacy isn’t about blocking access. It’s about building skills. Teaching students to read Wikipedia like a detective, write like a historian, and contribute like a citizen.

That’s not just good teaching. It’s necessary.

Can students cite Wikipedia in academic papers?

Most academic instructors still discourage citing Wikipedia directly because it’s a summary, not a primary source. But students can cite the original sources listed in Wikipedia’s references. The goal isn’t to use Wikipedia as a source-it’s to use it to find better ones.

Is Wikipedia accurate enough for college-level work?

Studies show Wikipedia’s accuracy on scientific topics is close to that of Encyclopedia Britannica. A 2021 analysis in Nature found that Wikipedia’s science articles had a 3.5% error rate, compared to Britannica’s 2.8%. The difference isn’t significant-but the transparency is. Wikipedia shows its edits. Traditional encyclopedias don’t.

Do librarians edit Wikipedia themselves?

Many do. Librarians are among the most active academic contributors to Wikipedia. They fix errors, add citations, and improve underrepresented topics. Some universities even have official "Wikipedian in Residence" roles. Their edits aren’t about promoting the library-they’re about improving public knowledge.

What if a student’s Wikipedia edit gets deleted?

It happens. But that’s part of the lesson. Wikipedia’s community reviews edits based on sources and policy, not authority. A student’s edit might be removed because it lacked citations-not because it was "wrong." That teaches students that evidence matters more than opinion. It’s not failure. It’s feedback.

How do librarians get trained to teach with Wikipedia?

The Wikimedia Foundation offers free online training modules for educators. Many universities host workshops, and librarians can earn a "Wikipedia Educator" badge. The University of Michigan’s library has a full curriculum, including lesson plans, rubrics, and student handouts-all freely available online.