On The Signpost, the Wikipedia community newspaper, readers don’t just read-they shape what gets written next. Every week, hundreds of editors, volunteers, and longtime contributors leave comments, fill out surveys, and reply to polls. This isn’t passive consumption. It’s a living feedback loop that keeps Wikipedia’s public face honest, accurate, and responsive.

Surveys That Actually Change Things

Every month, The Signpost runs a short survey on topics like recent policy changes, new tools, or controversial edits. These aren’t vanity metrics. They’re used by the Wikimedia Foundation’s volunteer teams to decide what to fix next.

In October 2025, a survey asked readers: "Do you feel the recent anti-harassment tools are helping you edit safely?" Over 1,200 responses came in. The results showed a 40% drop in reported harassment among users who used the new blocking interface-but 68% of new editors still didn’t know the tools existed. That feedback led to a new onboarding tutorial embedded directly into the edit screen for first-time contributors.

These surveys are simple. Usually five questions or fewer. They appear in the newsletter and on the front page of The Signpost for 72 hours. Responses are public, anonymized, and tagged by user experience level: "new," "regular," or "longtime." That way, the team knows if a change helps beginners or just veterans.

Comments Aren’t Just Noise-They’re Data

Every article on The Signpost has a comment section. But unlike most news sites, these aren’t just opinions. They’re structured feedback.

When a piece ran in November 2025 about the decline in active editors, the top comment wasn’t a rant. It was a user with 15 years of editing experience who wrote: "I stopped editing because the talk pages feel like courtrooms. No one listens unless you cite three policies." That exact phrase was pulled into a internal report. Within weeks, the Community Health team launched a pilot program called "Talk Page Mediators"-volunteers trained to help new editors navigate disputes without fear.

Comments are monitored by a small team of volunteer moderators. They tag them: "suggestion," "error," "concern," or "praise." Over 80% of suggestions that get tagged "high priority" by three or more users end up on the weekly agenda of the Wikipedia Editorial Council.

One of the most impactful comments came from a user who said: "I don’t edit because I don’t trust the sources cited. If you show me where the citation came from, I’ll fix it." That led to a new feature: clickable "Source Trail" links under every cited fact in Signpost articles, showing the full edit history of the reference.

The Feedback Loop in Action

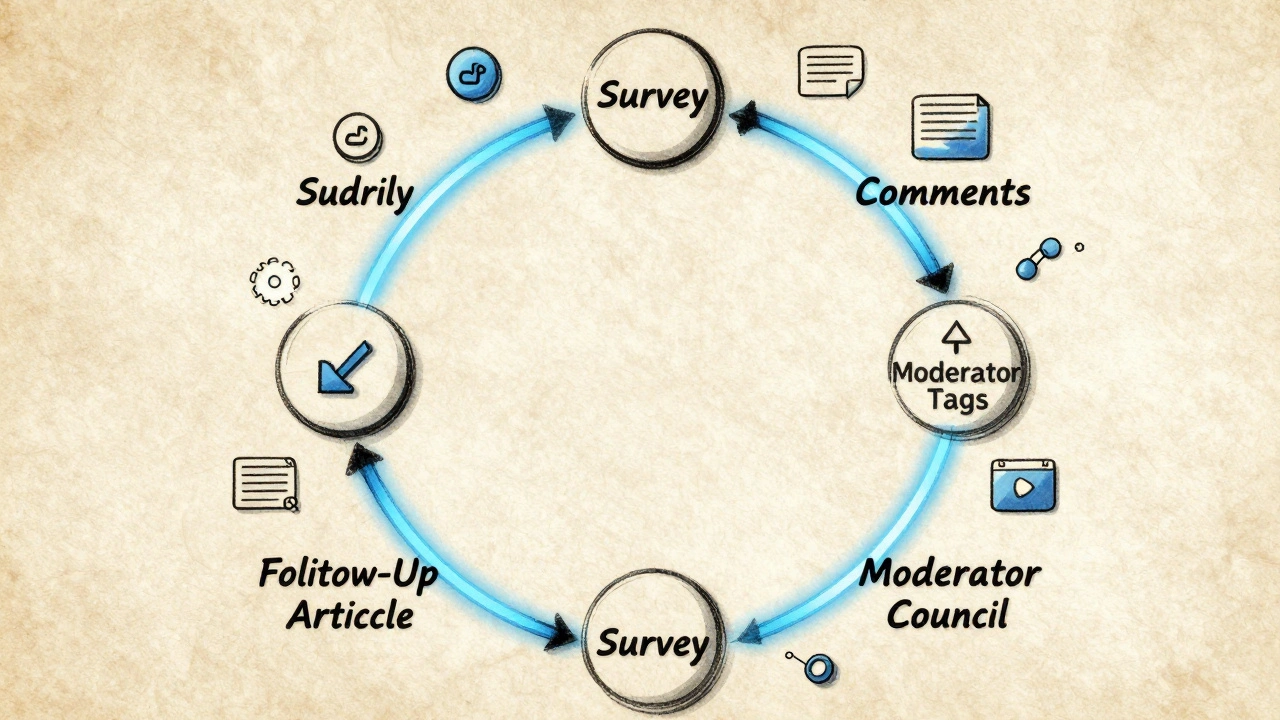

Here’s how it actually works, step by step:

- A story is published on The Signpost about a controversial change, like the new citation policy.

- Readers comment, take the survey, and share the article in their edit-a-thon groups.

- Volunteer moderators tag and summarize key themes from comments and survey responses.

- These summaries go to the Wikipedia Editorial Council every Monday morning.

- Based on the feedback, the Council votes to adjust the policy, create a help page, or launch a training video.

- Two weeks later, The Signpost publishes a follow-up: "What We Heard, What We Did."

This loop has been running since 2018. And it’s not perfect-but it’s rare. Most news outlets ignore feedback. Wikipedia’s community newspaper doesn’t just listen-it acts.

What Happens When Feedback Is Ignored

There have been failures. In March 2024, a story about declining article quality got over 500 comments, mostly from experienced editors saying the same thing: "We need better quality control tools, not more talk pages." The editorial team didn’t respond. The next month, survey participation dropped by 35%. People stopped believing their input mattered.

It took three months and a public apology from the editor-in-chief to rebuild trust. Since then, every article must include a "Feedback Status" box at the bottom: "We received X comments. Y were flagged as high priority. Z actions taken." Transparency became non-negotiable.

Why This Matters Beyond Wikipedia

The Signpost’s feedback system isn’t just useful for Wikipedia. It’s a model for how any large, volunteer-driven community can stay aligned with its users.

Other open-source projects-like LibreOffice and the Mozilla Foundation-have started copying the model. They now run their own "Signpost-style" newsletters and embed surveys directly into their user dashboards.

The key insight? People will give honest feedback if they know it leads to action. And they’ll keep giving it if they see the results.

How You Can Join the Loop

If you edit Wikipedia, you’re already part of this system. But here’s how to make your voice count:

- Read The Signpost every week. It’s free, no login needed.

- Reply to surveys when they pop up. Even one answer helps.

- Leave comments that are specific: "I tried the new tool and it crashed when I uploaded a 50MB file" is better than "This is broken."

- Tag your feedback with context: "new editor," "mobile user," "researcher." That helps the team prioritize.

- Share the survey with others. The more voices, the clearer the signal.

You don’t need to be an expert. You just need to care enough to speak up.

What’s Next

The Signpost team is testing a new feature: real-time feedback widgets on articles. Imagine reading a story about a recent edit war-and clicking a button to say, "I’ve seen this before, here’s what happened last time." That input gets added to a public timeline, visible to editors working on the same topic.

They’re also building an AI tool that scans comments and surveys for emerging trends. It doesn’t replace humans-it flags patterns humans might miss. Like a sudden spike in comments about citation formatting errors among non-English editors. That’s how a small issue becomes a global fix.

This isn’t about popularity contests. It’s about building something that lasts. And it only works if people who use it-really use it-tell the truth about how it feels.