Wikipedia is the largest encyclopedia ever built - and it’s built by people. Over 1.5 billion people visit it every month. But behind every edit, every article, every comment, there’s a real human. And when researchers study Wikipedia, they’re not just looking at text - they’re studying people. That’s where things get messy.

What Happens When You Study Wikipedia Data?

Researchers use Wikipedia data to understand how knowledge is created, how misinformation spreads, how gender bias shows up in biographies, and even how political views shape article content. They scrape edit histories, analyze user talk pages, track IP addresses, and map collaboration networks. All of this is public. But public doesn’t mean harmless.

Take the 2015 study that analyzed Wikipedia edits to predict users’ political leanings. It used edit timestamps, article topics, and username patterns to assign political labels to editors. Some of those editors were volunteers who had no idea their editing habits were being used for research. One person, a high school teacher in Ohio, found out years later that their edits to articles about climate change had been labeled as "liberal" in a published paper. They never consented. They didn’t even know they were part of a dataset.

This isn’t rare. It’s standard practice.

Public Data Isn’t Consent

Wikipedia’s content is licensed under Creative Commons. That means anyone can reuse articles. But that license doesn’t cover the people behind the content. Editing a page doesn’t mean you agree to be studied. You’re not signing up to be a research subject. You’re just trying to fix a typo or add a citation.

Researchers often say, "It’s all public data." But public data isn’t the same as public consent. A grocery store receipt is public if you leave it on the counter. That doesn’t mean someone can scan thousands of receipts, track your buying habits, and publish a report on your diet - without telling you.

Wikipedia editors aren’t lab rats. They’re volunteers. Many are elderly, disabled, or from countries with weak privacy protections. Some edit under pseudonyms because they fear retaliation. A teacher in Iran edits articles about human rights under a fake name. A survivor of domestic violence in Texas edits articles about abuse resources to make sure the information is accurate. If their editing patterns are linked back to them - even indirectly - their safety could be at risk.

How Researchers Anonymize - and Still Fail

Most academic papers claim they "anonymized" their data. They remove usernames. They replace IP addresses with hashed codes. They aggregate edits into groups. Sounds safe, right?

Not always.

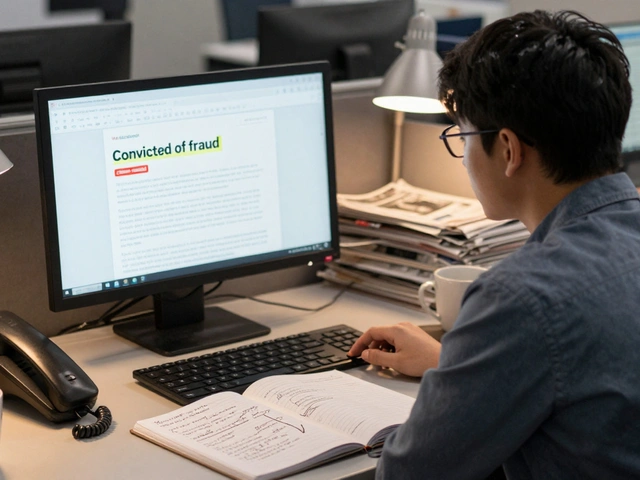

In 2020, a team at a European university released a dataset of 12 million Wikipedia edits. They removed names and IPs. But they kept timestamps, article titles, and edit lengths. A journalist from The Guardian cross-referenced the data with public court records and traced edits back to three individuals - including a whistleblower who had anonymously edited articles about corruption in their government. The researchers hadn’t intended to expose anyone. But the data was still identifiable.

Why? Because behavior is unique. The way someone edits - the time of day, the type of articles they fix, how often they revert changes - creates a digital fingerprint. Combine that with other public data, and anonymity vanishes.

There’s no such thing as perfect anonymization when you’re dealing with human behavior.

Who Gets Hurt When Ethics Are Ignored?

The biggest risk isn’t to the researchers. It’s to the editors.

Women, LGBTQ+ individuals, activists, and people from marginalized communities are overrepresented among Wikipedia’s most active editors - and also among those most likely to face harassment. When researchers publish findings that link editing patterns to identity, they can accidentally out people.

One study linked edits to articles about transgender rights with usernames that were clearly gendered. The paper didn’t name anyone. But it included enough detail that readers could guess who edited what. One editor received death threats after the paper was shared on social media. They stopped editing. That’s not just a loss for Wikipedia - it’s a loss for public knowledge.

And it’s not just about safety. It’s about trust. If editors believe their work is being mined for research without their knowledge, they’ll pull back. Participation drops. The encyclopedia becomes less diverse, less accurate, less representative.

What Should Researchers Do Instead?

There are better ways. And they’re not that hard.

- Ask for consent. If you’re studying a group of editors - like those who edit medical articles - send them a clear message: "We’re doing research on how medical knowledge is updated. Would you be okay if we included your edits in our study?" Offer an opt-out. Make it easy.

- Use aggregated data only. Don’t release datasets with timestamps, edit sequences, or unique behavioral patterns. Publish totals: "58% of edits to cancer articles came from users with fewer than 10 edits total." Not "User X edited the breast cancer article 47 times between 2021 and 2023."

- Apply the "right to be forgotten" principle. If someone asks to be removed from a dataset, honor it. Even if their data is already published. Pull the paper. Issue a correction. It’s the ethical thing to do.

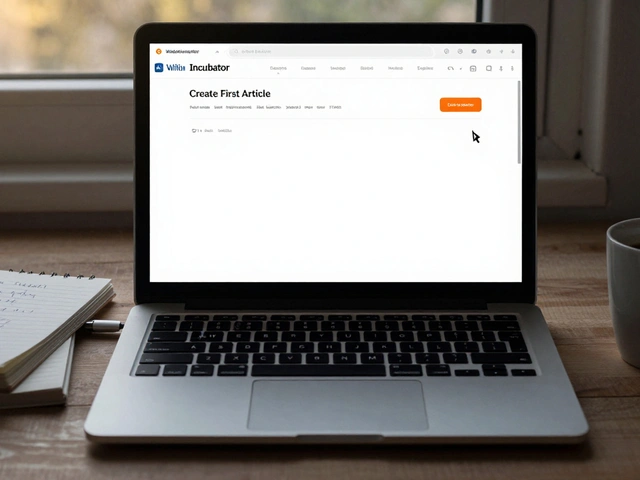

- Work with Wikipedia’s research team. The Wikimedia Foundation has a Research and Data team that reviews studies. They can help you design ethical research. Use them. They’re not there to block you - they’re there to protect the community.

Some researchers are already doing this. A 2023 study on gender bias in biographies only used aggregated data from the top 10,000 most-edited pages. They didn’t track individual users. They published their methods openly. And they included a note: "No individual editor was identified or contacted without explicit permission." That’s the standard.

The Bigger Problem: No Rules

There’s no formal ethics board for Wikipedia research. No IRB (Institutional Review Board) reviews these studies. Universities approve them because they’re "public data." Journals publish them because they’re "novel findings." But Wikipedia isn’t Twitter. It’s not a public forum where you expect to be analyzed. It’s a collaborative knowledge project built on trust.

The Wikimedia Foundation has guidelines - but they’re soft. They say researchers should "respect privacy" and "avoid harm." But there’s no enforcement. No penalty for breaking them. No way to know if a study followed the rules.

That’s why some scholars are calling for a Wikipedia Research Ethics Charter. A real set of rules, signed by universities, journals, and funding agencies. Rules that require consent, anonymization standards, and harm assessments before any study begins.

What You Can Do

If you’re a student or researcher working with Wikipedia data:

- Ask yourself: "Could this reveal someone’s identity?" If yes, stop.

- Ask: "Would I want my edits studied like this?" If not, change your method.

- Always check with the Wikimedia Research team before starting.

- Don’t publish raw datasets. Publish summaries.

- Include an ethics statement in every paper. Say what you did to protect editors.

If you’re an editor:

- Know your rights. You can ask to be removed from any study.

- If you see a paper that identifies editors, report it to the Wikimedia Foundation.

- Use a username. Don’t use your real name. Even if you think you’re safe.

Wikipedia Isn’t Just a Website - It’s a Community

Wikipedia’s power comes from its people. Not its servers. Not its algorithms. The 100,000 volunteers who show up every day to fix errors, add sources, and fight bias.

When researchers treat Wikipedia like a data mine, they’re not just breaking ethics - they’re breaking trust. And once trust is gone, the encyclopedia starts to unravel.

Good research doesn’t need to exploit people. It needs to respect them. The best findings come from collaboration, not extraction.

Is it legal to study Wikipedia data without consent?

Yes, it’s often legal - but that doesn’t make it ethical. Wikipedia’s content is publicly licensed, but the people behind the edits aren’t. Legal doesn’t mean right. Many researchers have faced backlash, retractions, and professional consequences for studies that violated community trust, even if they didn’t break the law.

Can Wikipedia editors opt out of research?

There’s no official opt-out system built into Wikipedia, but editors can request removal from a study. The Wikimedia Foundation supports this right. If a researcher refuses to remove your data, you can file a formal complaint with the Foundation. Many researchers will comply if asked - especially if they’re following ethical guidelines.

Do universities require ethics approval for Wikipedia research?

Most don’t - and that’s a problem. Because Wikipedia data is public, many university IRBs classify it as "non-human subjects research." But this ignores the real-world harm that can come from identifying individuals. More universities are starting to require ethics reviews for digital research, but it’s not yet standard.

What’s the difference between studying Wikipedia articles and studying Wikipedia editors?

Studying articles is like studying books - you’re analyzing text. Studying editors is like studying the writers - you’re analyzing behavior, identity, and patterns that can reveal who they are. The latter carries far more risk. Most ethical studies focus on articles, not on tracing edits back to individuals.

Are there any tools to help researchers study Wikipedia ethically?

Yes. The Wikimedia Foundation offers the Research Dashboard, which provides aggregated, anonymized data on edits, user activity, and article trends. It’s designed to prevent re-identification. Researchers are strongly encouraged to use it instead of scraping raw data. Tools like WikiStats and the Edit Counter API are safer alternatives to direct data extraction.

Wikipedia’s future depends on the people who build it. If we want accurate, diverse, trustworthy knowledge, we have to protect the humans behind it - not just the data they leave behind.