Wikipedia doesn’t have a board of directors making top-down decisions. Instead, its rules evolve through quiet, messy, and sometimes slow conversations between thousands of volunteers. At the heart of this process is the Request for Comment (a formal process on Wikipedia where editors propose changes to policies or guidelines and invite community feedback, RFC). If you’ve ever wondered how a rule like "no original research" or "neutral point of view" gets updated, it almost always starts with an RFC. This isn’t a vote. It’s not a petition. It’s a structured, public, and open discussion that can take weeks-or months-to complete.

What an RFC Actually Is

An RFC is not a proposal you submit and wait for approval. It’s a living document. You write it, post it on a dedicated page, and then wait for people to respond. The goal isn’t to win an argument-it’s to find common ground. Editors from different backgrounds, with different experiences, weigh in. Some are longtime contributors who’ve seen policy shifts before. Others are new editors who’ve run into a problem firsthand. The best RFCs don’t push a single solution. They lay out the issue, explain why it matters, and invite alternatives.

For example, in 2023, an RFC on the Biographies of living persons policy asked whether editors should be required to cite at least two independent sources before adding sensitive claims about public figures. Over 120 editors participated. Some cited cases where single-source claims led to defamation lawsuits. Others warned that stricter rules might silence legitimate reporting from small outlets. The discussion lasted 28 days. The final policy didn’t change overnight-but the community now had a clearer understanding of what "reliable sources" really means in practice.

How the Process Works

There’s no official form. But there’s a pattern. Here’s how most successful RFCs unfold:

- Start with a clear problem. Don’t say "I think we should change X." Say: "Currently, editors are removing citations from articles about politicians because they’re from blogs. This creates inconsistency. Here are five recent examples."

- Post it on the right page. Policy RFCs go to Wikipedia:RFC. Guidelines go to Wikipedia:GFC (Guideline for Comment). Don’t mix them.

- Set a deadline. Most RFCs run for 14 to 30 days. Too short, and people miss it. Too long, and it stalls. The standard is 21 days.

- Invite diverse voices. Tag editors from different regions, language backgrounds, and experience levels. Don’t just ping your friends.

- Summarize the discussion. As comments pile up, update the RFC page with a running summary. Highlight agreement, disagreement, and new ideas.

- Close with a consensus statement. The closing editor doesn’t declare a winner. They write: "The consensus appears to be X. A few editors remain concerned about Y. The policy will be updated to reflect X, with a note added about Y for future review."

There’s no magic number of votes. A single well-reasoned argument from a trusted editor can carry more weight than 50 generic "I agree" comments. What matters is the quality of reasoning, not the quantity of signatures.

Typical Timelines

Wikipedia policy changes aren’t fast. They’re deliberate. Here’s what you can expect:

- Pre-RFC phase (1-4 weeks): Most policy ideas start as informal talk on talk pages, mailing lists, or village pumps. If an idea gains traction, someone drafts a formal RFC.

- Active discussion (14-30 days): This is the core window. Comments flood in. Some are thoughtful. Some are hostile. The best RFCs filter out noise by citing specific policy sections and past decisions.

- Closing and implementation (1-7 days): Once discussion ends, a neutral editor writes a summary. If consensus is clear, the policy page is edited. If not, the RFC may be reopened, extended, or archived as "no consensus."

- Post-change monitoring (weeks to months): Changes aren’t final until they’re tested. Editors watch for unintended consequences. A policy change that looks good on paper might cause confusion in practice. That’s why many RFCs include a "review in 6 months" note.

Take the 2022 RFC on "citing social media." It took 4 months from first idea to final policy update. The first 3 weeks were spent just agreeing on what counts as "social media." Then came 30 days of discussion. Then 10 days of drafting the new wording. Then another month of testing edits on high-traffic articles. The final rule? "Twitter/X, Facebook, and Instagram posts may be used as sources only if they are published by official accounts and contain verifiable, non-opinion statements."

Why It Takes So Long

Wikipedia isn’t a startup trying to move fast and break things. It’s a global reference work with 1.8 billion monthly readers. A bad policy change can mislead millions. That’s why the process is slow. It’s not broken-it’s designed to be resistant to sudden shifts.

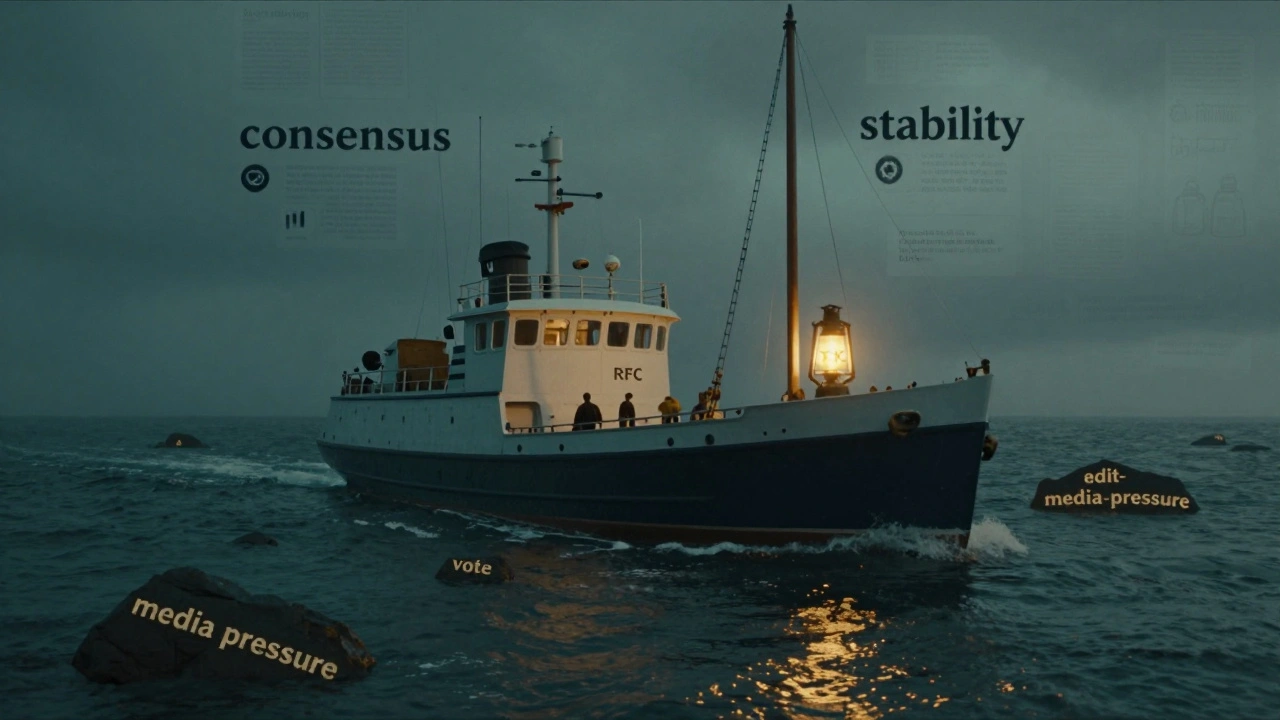

Think of it like a ship. It doesn’t turn on a dime. If a small group of editors pushes for a radical change, the community will push back. That’s not bureaucracy. That’s protection. The system favors stability. It demands evidence. It asks: "Has this been tried before? What went wrong? Who was harmed?"

There’s also a cultural norm: don’t rush consensus. If an RFC closes with 75% agreement but 20% of the comments are strong objections, the change is usually delayed. That’s because Wikipedia’s policies aren’t just rules-they’re social contracts. Breaking them risks trust.

What Doesn’t Work

Many editors think they can force a policy change by:

- Starting a vote (they don’t work-Wikipedia doesn’t do majority rule)

- Editing articles to "prove" a policy is broken (that’s edit-warring, not reform)

- Getting celebrities or media outlets to weigh in (this distracts from the real issue)

- Threatening to quit or delete content (this triggers community backlash)

Instead, successful reformers do the opposite. They:

- Document real-world problems with links to edit histories

- Reference past RFCs that reached similar conclusions

- Offer clear, testable alternatives

- Stay calm, even when others don’t

One editor in 2024 changed how Wikipedia handles climate change denial by not arguing about science. They compiled a list of 37 recent articles where climate misinformation had been added and removed. They showed how often editors had to revert edits. They didn’t say "climate change is real." They said: "This is how often the policy is being tested. Here’s the cost to the encyclopedia."

Real Examples of RFC-Driven Changes

Here are three recent policy shifts that came from RFCs:

- 2023: "No citation needed" tags removed from high-risk articles. After an RFC showed that these tags were being used to silence legitimate sourcing in articles about politicians and corporations, the policy was updated to require citations on all contentious claims.

- 2022: "Notability" guidelines clarified for non-Western figures. An RFC from editors in India, Nigeria, and Brazil showed that Western media bias was causing non-Western public figures to be deleted. The policy now requires "significant coverage in multiple independent sources," not just English-language ones.

- 2021: "Conflict of interest" rules tightened for PR firms. After a series of scandals involving paid editors, an RFC led to a ban on PR firms editing articles about their clients-even if they claim to be "volunteers."

What Happens After an RFC?

Once a policy changes, it doesn’t magically fix everything. Editors still need to learn the new rule. Articles need to be updated. New editors need to be trained. That’s why many RFCs include a "next steps" section:

- Update policy documentation

- Create a help page or tutorial

- Tag relevant articles for review

- Announce the change on the Village Pump

Some changes take years to fully embed. For example, the 2015 RFC on "verifiability over truth" is still being taught to new editors today. The idea-that Wikipedia doesn’t decide what’s true, but only what’s documented-wasn’t widely understood until editors started using it in edit summaries and talk page discussions.

How to Get Involved

You don’t need to be an admin. You don’t need to have edited 1,000 articles. You just need to care enough to speak up. If you’ve seen a policy cause confusion, here’s how to start:

- Find a specific example of the problem. Link to the edit history.

- Read past RFCs on the topic. Don’t repeat old arguments.

- Write a clear, neutral RFC. Use plain language.

- Post it. Wait. Listen. Revise.

Wikipedia’s policies aren’t carved in stone. They’re written in ink-and that ink is supplied by people like you.

Can anyone start an RFC on Wikipedia?

Yes. Any registered user can start an RFC. You don’t need special status, edit count, or approval. The only requirement is that you’re not banned or blocked. However, RFCs from new editors are more likely to be ignored if they’re vague, emotional, or lack examples. The best RFCs are calm, specific, and cite real edits.

Do RFCs always lead to policy changes?

No. Many RFCs end with "no consensus." That’s not a failure-it’s part of the system. If there’s strong disagreement, or if the proposed change would cause more harm than good, the policy stays as-is. Sometimes, the discussion itself improves understanding, even if nothing changes. Wikipedia values stability over constant change.

How long does an RFC stay open?

Most RFCs run for 14 to 30 days, with 21 days being the most common. The person starting the RFC suggests a closing date, but it’s not binding. If discussion is active and productive, it can be extended. If it’s dead, it can be closed early. The goal is to let enough people participate, not to hit a timer.

Can an RFC be ignored or deleted?

No. RFCs are permanent records. Even if a policy change is rejected, the RFC page remains archived. It becomes part of Wikipedia’s history. Future editors can look back at old RFCs to understand why certain rules exist or why attempts to change them failed. Deleting an RFC is considered vandalism.

What’s the difference between an RFC and a vote?

A vote assumes majority rule: 51% wins. Wikipedia rejects that. An RFC looks for consensus: enough agreement that the change feels right to the community, even if not everyone agrees. A vote can be manipulated. A consensus discussion reveals deeper concerns. One editor with a well-reasoned objection can stop a change, even if 90% support it.