Wikipedia doesn’t work like a regular website. You don’t land on a page and stay there. You jump. You click. You get redirected. And most of the time, you don’t even notice it.

Why Wikipedia Redirects Are Everywhere

Every day, millions of people search for things like ‘Eiffel Tower’ or ‘iPhone 15’ and end up on Wikipedia. But what if they type ‘Eiffel Tower Paris’? Or ‘Apple phone’? Or even misspell ‘Eiffel’ as ‘Eifel’?

That’s where redirects come in. Wikipedia uses them to make sure no matter how you search, you still get to the right page. There are over 1.2 billion redirects active on Wikipedia as of 2025. That’s more than one redirect for every three articles.

These aren’t just simple typos. Redirects cover synonyms, abbreviations, historical names, and even common misunderstandings. For example:

- ‘NYPD’ redirects to ‘New York City Police Department’

- ‘T-Rex’ redirects to ‘Tyrannosaurus’

- ‘Covid’ redirects to ‘COVID-19’

- ‘Barack Obama’ redirects to ‘Barack Obama’ (yes, even the exact match has a redirect system behind it)

Behind the scenes, every redirect is a deliberate choice made by editors. They don’t just auto-generate them. Each one is reviewed to make sure it’s accurate, useful, and doesn’t create confusion.

How Users Actually Move Through Wikipedia

Most people think they’re reading Wikipedia from start to finish. But data from Wikimedia’s internal analytics shows something else: users bounce.

On average, a user visits 3.7 pages per session on Wikipedia. And nearly 68% of those visits start from a redirect - not from a search engine or a link on another site.

Here’s how it usually plays out:

- You Google ‘who invented the telephone’

- You click the top result: ‘Alexander Graham Bell’

- Wikipedia redirects you from ‘inventor of telephone’ to ‘Alexander Graham Bell’

- You read his bio, then click ‘telephone’ in the first paragraph

- You land on the ‘Telephone’ page, then click ‘history of telecommunications’

- You leave after 8 minutes.

This isn’t random. It’s a pattern. Users start with a question, get redirected to the answer, then follow links to related topics. Wikipedia’s structure turns a single search into a chain of discovery.

The Hidden Logic Behind Redirect Chains

Not all redirects are direct. Some are chained. That means one redirect points to another redirect, which then points to the final page.

For example:

- ‘iPhone 15 Pro Max’ → redirects to → ‘iPhone 15 Pro Max (2023)’ → redirects to → ‘iPhone 15 Pro Max’

Why? Because editors update redirects when article titles change. If a page gets renamed to include the year (like ‘iPhone 15 Pro Max (2023)’), old links still need to work. So they point to the new title - which then points to the current, clean version.

Wikipedia’s software tracks these chains. If a redirect chain is longer than three steps, it flags it for review. Too many hops slow down the user. Too many chains mean confusion.

As of 2025, less than 0.3% of redirects are chained more than twice. That’s intentional. Wikipedia’s team keeps redirect paths as short as possible.

What Happens When Redirects Go Wrong

Redirects are usually invisible. But when they break, people notice.

One common mistake: redirect loops. That’s when Page A redirects to Page B, which redirects back to Page A. The browser gets stuck. Users see an error like ‘Too many redirects’ - and they leave.

Another issue: ambiguous redirects. For example, ‘JFK’ could mean John F. Kennedy, John F. Kennedy International Airport, or even a basketball player. If a redirect points to the wrong one, users get frustrated.

Wikipedia has tools to catch these. Editors use the ‘Special:WhatLinksHere’ page to see which pages link to a redirect. If a redirect has too many incoming links but leads to the wrong place, it gets flagged.

There’s also a community of volunteer editors who monitor redirect quality. They’re called ‘redirect caretakers.’ They fix broken links, merge duplicate redirects, and clean up outdated ones. In 2024 alone, they resolved over 850,000 redirect issues.

How Redirects Shape What You See

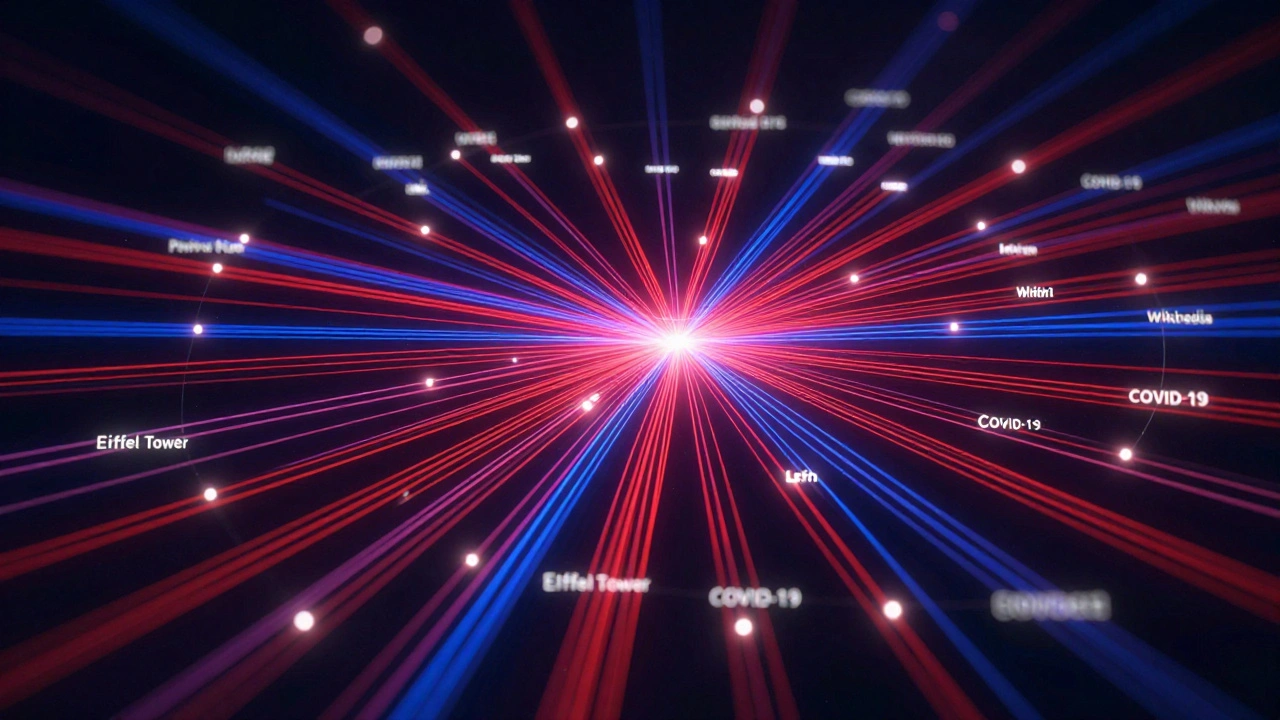

Redirects don’t just help you find pages - they shape what topics get attention.

Think about it: if you type ‘climate change,’ you go to the main article. But if you type ‘global warming,’ you get redirected there too. That means both terms feed traffic into one page.

That’s powerful. It means Wikipedia can combine search volume from multiple terms into one central hub. The ‘Climate change’ page gets more views, more edits, and more authority because it collects traffic from 12 different variations.

Compare that to a page with no redirects. ‘Anthropogenic global warming’ might be the technically correct term, but if no one types it, the page stays quiet. Editors often create redirects to boost visibility for underused but accurate terms.

This is why Wikipedia’s traffic doesn’t follow a normal bell curve. A few pages - like ‘United States,’ ‘2024,’ or ‘Artificial intelligence’ - get hundreds of millions of views. Why? Because they’re the end point of dozens, sometimes hundreds, of redirects.

What Redirects Reveal About Human Behavior

Wikipedia’s redirect data is a mirror of how people think - and how they get things wrong.

For example, ‘KFC’ redirects to ‘Kentucky Fried Chicken.’ That’s obvious. But ‘Fried chicken’ redirects to ‘Chicken’? No. It redirects to ‘Fried chicken’ - a separate page. Why? Because people search for it as a dish, not just as an ingredient.

Even slang matters. ‘Sick’ (as in ‘that’s sick!’) redirects to ‘Slang’ - not ‘illness.’ ‘Lit’ redirects to ‘Slang.’ ‘Yeet’ redirects to ‘Internet slang.’

Wikipedia’s redirect system is one of the largest real-time studies of language use on the planet. Every redirect is a data point about how people phrase questions, make mistakes, or use local terms.

Researchers at Stanford and MIT have used this data to study how language evolves. They found that new slang terms become redirects within 6-12 months of going viral. TikTok trends like ‘girl dinner’ or ‘quiet quitting’ show up as redirects within weeks.

What You Can Learn From Wikipedia’s Traffic Patterns

If you’re writing content - whether it’s a blog, a product page, or a school paper - Wikipedia’s redirect system teaches you something important:

- People don’t search for perfect terms. They search for what they know.

- Anticipate misspellings, abbreviations, and casual phrasing.

- One main topic can absorb traffic from many variations - if you structure it right.

- Redirects aren’t just technical fixes. They’re user experience tools.

Wikipedia doesn’t force users to learn its rules. It adapts to them. That’s why it’s still the most visited reference site in the world - even in 2025, when AI chatbots are everywhere.

You don’t need to build a Wikipedia to use this idea. Just ask: ‘What are 5 ways someone might search for this?’ Then make sure your content answers all of them.