Wikipedia claims to be the free encyclopedia that anyone can edit. But if you’re from a community that passes down history through storytelling, song, or ritual, you might find your knowledge doesn’t count. The rules that make Wikipedia seem neutral often silence voices that don’t fit its rigid structure. Oral traditions, passed down for generations, are dismissed as "unverifiable." Local knowledge-like medicinal plant use by Indigenous healers or ancestral land management practices-is labeled "original research" and deleted. This isn’t an accident. It’s baked into the system.

What Wikipedia Considers "Reliable Sources"

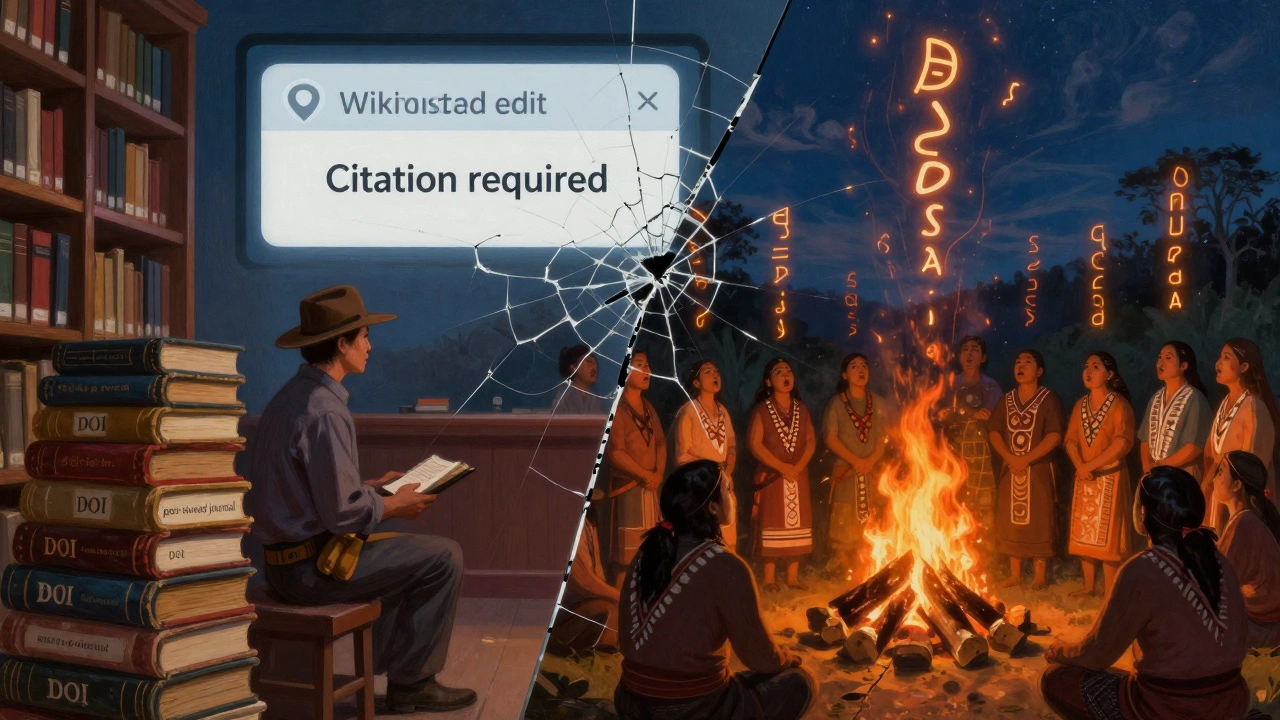

Wikipedia’s core policy requires all claims to be backed by published, peer-reviewed, or mainstream media sources. That sounds fair-until you realize most oral traditions don’t appear in books or journals. A Navajo elder explaining seasonal migration patterns through story isn’t citing a 2018 academic paper. A Māori community describing sacred sites through chants doesn’t have a DOI number. Yet these are the very sources that hold centuries of ecological and cultural wisdom.

Wikipedia’s reliance on printed texts privileges Western academic norms. It assumes knowledge must be written, dated, and published by institutions with funding and access to global publishing networks. In many parts of the world, knowledge is held in the body-in dance, in song, in silence. These aren’t less valid. They’re just not compatible with Wikipedia’s checklist.

How "No Original Research" Kills Local Knowledge

One of Wikipedia’s most damaging policies is "no original research." It blocks editors from adding information that hasn’t already appeared in a published source. That means if a community has used a specific plant to treat fever for 300 years, but no scientist has published a study on it, Wikipedia won’t list it-even if every elder in the village confirms it.

Take the case of the Yucatec Maya. Their traditional use of the chaya plant for anemia was removed from Wikipedia because no Western medical journal had validated it. Meanwhile, the same plant’s chemical composition was added after a single 2012 lab study-even though the Maya had been using it safely for centuries. The policy doesn’t protect truth. It protects a narrow definition of what counts as proof.

Original research isn’t just about inventing facts. It’s about trusting lived experience. When a community shares knowledge that hasn’t been peer-reviewed by a university, Wikipedia treats it as noise. Not as wisdom.

Why Oral History Gets Deleted

Oral traditions are often flagged as "unsourced" or "anecdotal." But what’s an anecdote if not a story passed down? In Ghana, the Akan people use proverbs to teach history, ethics, and environmental stewardship. One proverb, "The tree that bends does not break," encodes lessons about resilience and land use. But if you try to add that to Wikipedia, it gets deleted for lacking a citation.

Wikipedia’s editors, mostly from urban, Western, educated backgrounds, don’t recognize oral forms as legitimate evidence. They don’t know how to listen. They look for footnotes, not elders. They want a PDF, not a story.

Studies from the University of Cape Town and the Smithsonian have shown that over 80% of oral history submissions to Wikipedia are rejected. Not because they’re false. Because they’re not written.

The Cost of Exclusion

When local knowledge disappears from Wikipedia, it doesn’t just vanish from a website. It vanishes from public memory. Students in Nigeria learn about African history from Wikipedia, not from their grandparents. Indigenous youth in Canada search for their ancestral practices and find nothing. The absence of their knowledge on the world’s most visited reference site sends a message: your history doesn’t matter.

It also affects real-world outcomes. Health workers in rural India rely on Wikipedia to understand traditional remedies. When those remedies are removed for lacking citations, people stop using them-not because they’re ineffective, but because they’re labeled unreliable. That’s not neutrality. That’s erasure.

And it’s not just about culture. Local ecological knowledge-like how to predict monsoon patterns from bird behavior, or how to rotate crops without chemical fertilizers-is being lost because it’s not documented in English-language journals. Climate scientists are now scrambling to recover this knowledge. But Wikipedia, the platform that could have preserved it, didn’t.

Who Gets to Decide What’s True?

Wikipedia’s policies are written by volunteers, but they’re dominated by a small group. Less than 1% of editors account for over 50% of edits. Most are men under 30, from North America and Europe. They speak English as a first language. They grew up with libraries, not elders.

These editors aren’t malicious. They’re trained to believe that verifiability equals truth. But truth isn’t just what’s written down. It’s what’s lived. It’s what’s remembered. It’s what’s sung.

When a community in Papua New Guinea tries to add information about their forest medicine, they’re told to cite a journal. But the nearest university is 200 miles away. The language of their knowledge isn’t English. The concept of a citation doesn’t exist in their culture. So they give up. And Wikipedia becomes a library that only accepts donations from certain countries, in certain languages, from certain kinds of people.

What Can Be Done?

Change is possible-but it requires rewriting the rules, not just adding exceptions.

- Accept oral testimony as a source-in contexts where written records are absent. This already happens in anthropology and ethnography. Why not here?

- Create community archives-Wikipedia could partner with Indigenous groups to host verified oral histories on separate, linked pages labeled "Community Knowledge" with clear disclaimers and cultural protocols.

- Train editors on cultural literacy-not just how to cite a book, but how to recognize oral forms, non-Western epistemologies, and the difference between anecdote and tradition.

- Allow non-English sources-if a local newspaper in Swahili or Quechua reports on a traditional practice, that’s a valid source. Not a footnote to English.

Some projects are already trying. The "Oral History Project" on Wikimedia Commons lets communities upload audio recordings with transcripts. The "Indigenous Knowledge Initiative" in Canada works with First Nations to co-create articles. But these are side projects. They’re not policy. They’re not mandatory.

Wikipedia doesn’t need to become a museum of folklore. It needs to become a living archive that reflects the full breadth of human knowledge-not just the kind that fits on a printed page.

Why This Matters Beyond Wikipedia

Wikipedia isn’t just a website. It’s the first place most people go to learn anything. It’s the default truth machine of the internet. When it excludes oral traditions and local knowledge, it doesn’t just lose content. It reshapes how the world understands truth itself.

If we accept that only written, Western, academic sources count, then we’re saying that cultures without writing are less intelligent, less organized, less worthy of preservation. That’s not just biased. It’s dangerous.

The real question isn’t whether oral knowledge is "reliable." It’s whether we’re willing to expand what reliability means.

Why doesn’t Wikipedia accept oral history as a valid source?

Wikipedia’s policies require sources to be published and verifiable, which traditionally means printed books, academic journals, or mainstream media. Oral traditions don’t meet that standard because they aren’t written down or indexed in databases. But this requirement favors Western, literate cultures and ignores systems of knowledge that have existed for millennia. The policy isn’t about accuracy-it’s about format.

Can Indigenous communities add their own knowledge to Wikipedia?

Yes, but it’s extremely difficult. Most submissions from Indigenous communities are flagged as "original research" or "unsourced" because their knowledge isn’t documented in English-language publications. Even when elders provide testimony, editors often don’t recognize it as valid evidence. Some communities have created their own Wikimedia projects, but these are exceptions, not policy.

Does Wikipedia have any policies that support cultural diversity?

Wikipedia has general policies on neutrality and cultural sensitivity, but they’re not enforced in practice. There’s no official policy that recognizes oral traditions, non-Western epistemologies, or community-based knowledge as valid sources. Without specific guidelines, editors default to Western academic standards, which systematically exclude non-literate knowledge systems.

Are there examples of local knowledge being erased from Wikipedia?

Yes. The traditional use of chaya leaves by the Yucatec Maya for anemia was removed because no Western medical journal had studied it. In Ghana, Akan proverbs about land use were deleted as "anecdotal." In Australia, Aboriginal fire management techniques were labeled "unverified" and removed, even though they’re now being adopted by government agencies. These aren’t isolated cases-they’re routine.

What’s the impact of excluding local knowledge from Wikipedia?

When local knowledge disappears from Wikipedia, it disappears from public understanding. Students, health workers, and policymakers rely on it as a primary source. If traditional remedies, ecological practices, or cultural histories aren’t there, people assume they don’t exist. This leads to loss of cultural identity, erosion of traditional practices, and even harm to public health when communities stop using effective remedies because they’re labeled "unreliable."