Wikipedia doesn’t just throw articles into a big pile. If it did, finding anything would be like searching for a single grain of sand on a beach. Instead, it uses a powerful, hidden system of categories and taxonomies to keep its 60 million+ articles organized, searchable, and connected. This isn’t just about labels-it’s the backbone of how millions of people find reliable information every day.

What Are Wikipedia Categories?

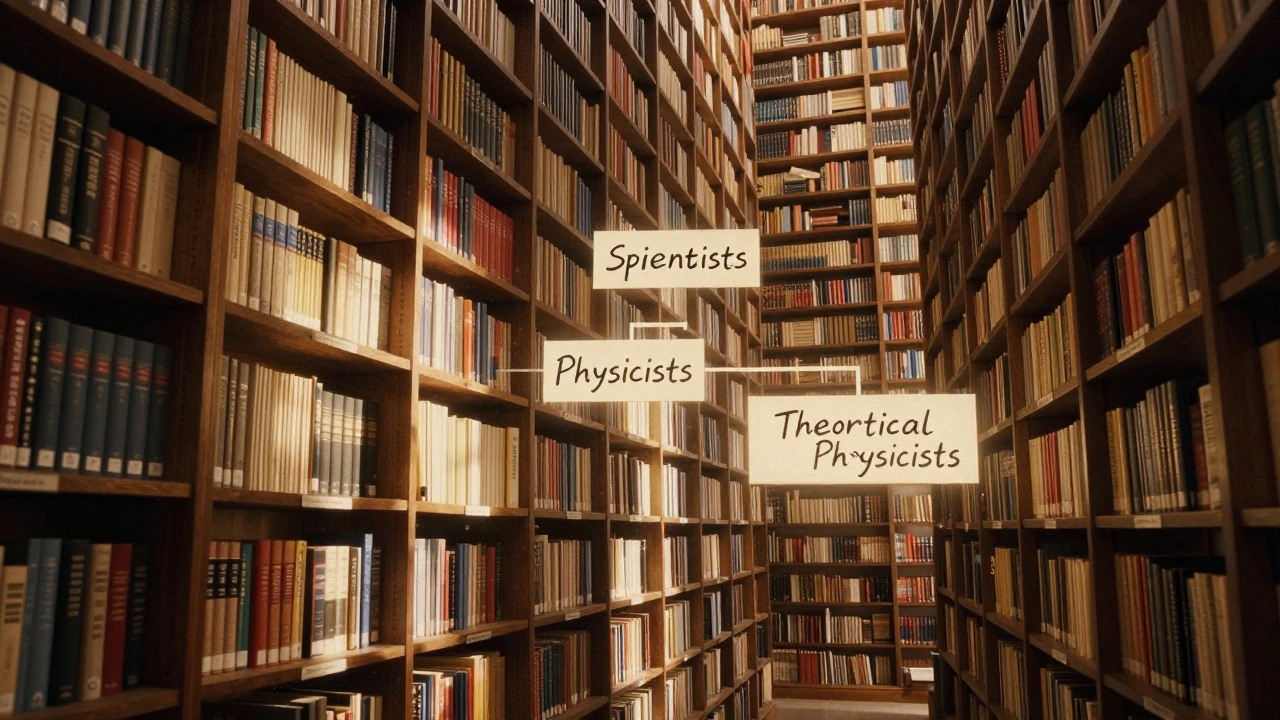

Categories are the most basic building block of Wikipedia’s organization. Think of them as folders in a filing cabinet. Every article can belong to one or more categories. For example, the article about Albert Einstein is categorized under Physicists, German scientists, Nobel laureates in Physics, and 20th-century scientists. These aren’t random. Each one helps users drill down from broad topics to specific ones.

Categories are created by editors, not algorithms. Anyone with an account can add a category to an article using a simple syntax: [[Category:Physicists]]. But there’s a catch-categories must follow naming rules. They’re lowercase, singular, and use standard English terms. No jargon. No abbreviations. That consistency is what makes the system work across 300+ language editions.

Categories also nest. The category Physicists is itself inside Scientists, which is inside Academics. This creates a hierarchy, letting users click upward to broader topics or downward to more specific ones. It’s like a map where each step reveals more detail.

The Taxonomy Behind the Scenes

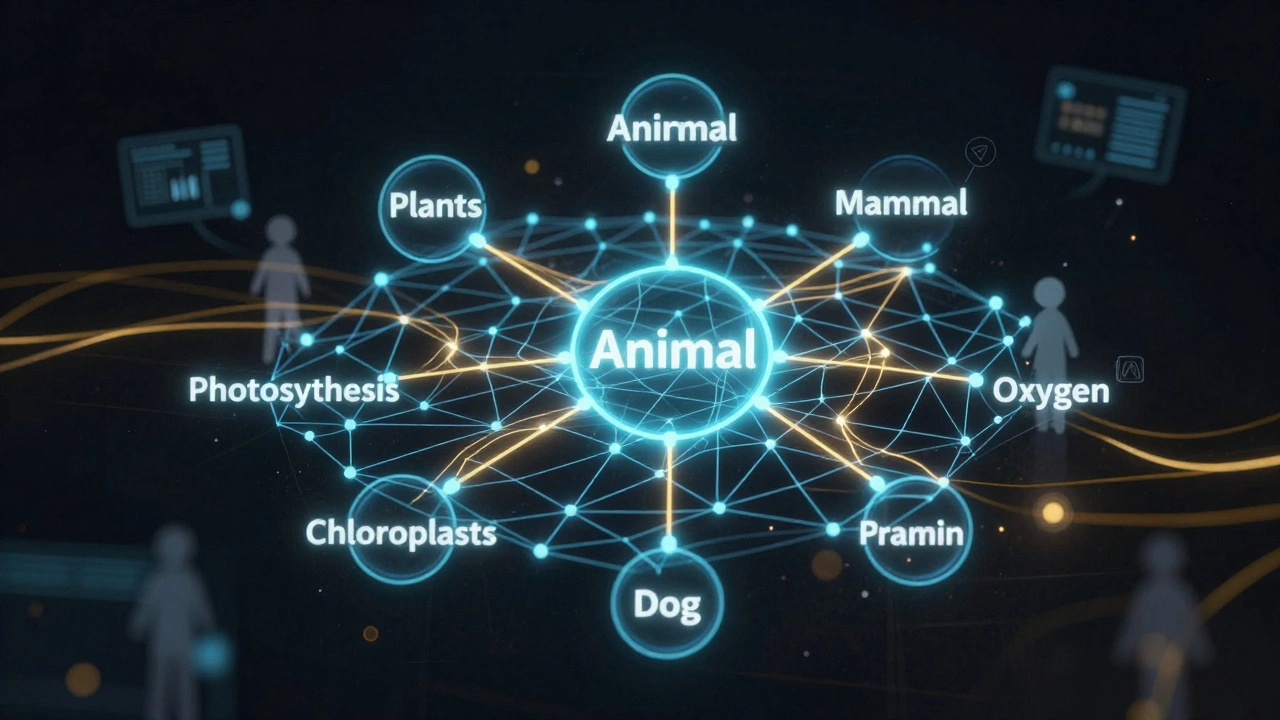

Categories alone aren’t enough. Wikipedia’s real power comes from its taxonomy-a structured system of relationships between concepts. A taxonomy isn’t just a list; it’s a web of how things relate. For example, a dog is a mammal, which is a vertebrate, which is an animal. Wikipedia doesn’t just tag articles with these labels-it builds connections that let you trace logical paths.

Wikipedia’s taxonomy isn’t formalized like a scientific classification, but it follows the same principles. It uses parent-child relationships, sibling groupings, and cross-references. The article on Photosynthesis links to Plants, Chloroplasts, Carbon dioxide, and Oxygen. These aren’t just random links. They’re intentional nodes in a knowledge graph that helps both readers and bots navigate the system.

Behind this is a tool called Category trees. These are automated visualizations that show how categories connect. Editors use them to spot gaps-like a category missing a parent, or a child category that should be merged. If you look at the category Computer science, you’ll see subcategories like Algorithms, Programming languages, and Artificial intelligence. Each one is carefully placed so that someone researching machine learning can find related topics without getting lost.

How Categories Help You Find Information

Most users never think about categories. But they’re the reason you can go from “I want to know about quantum computing” to “Show me all papers on quantum entanglement” in three clicks.

Let’s say you’re reading about Bitcoin. At the bottom of the page, you’ll see categories like Cryptocurrencies, Digital currencies, and Blockchain technology. Clicking Cryptocurrencies takes you to a list of over 200 other coins-each with its own article. You can then click into Blockchain technology and see how Bitcoin fits into the larger system. This isn’t just convenience-it’s discovery.

Wikipedia’s category system also powers its search. When you type “French Revolution,” the system doesn’t just match words. It looks at the categories the article belongs to, the categories of related articles, and even the categories of articles that link to it. That’s why you rarely get irrelevant results. The system understands context, not just keywords.

Even bots rely on this. Wikipedia’s automated tools use categories to flag articles that need work. If an article is in Articles needing cleanup and also in Biographies of living people, the bot knows to prioritize it. Categories turn messy data into actionable tasks.

Rules and Limitations

Wikipedia’s system isn’t perfect. It’s built by volunteers, not engineers. That means inconsistencies creep in. Some categories are too broad-People has over 2 million members. Others are too narrow-2007 births in Canada exists, but 2007 births in Ontario doesn’t. Editors debate whether to split, merge, or rename categories daily.

There are strict rules to keep order:

- Categories must be based on encyclopedic relevance, not personal interest.

- You can’t have a category just because something is “cool” or “popular.”

- Each category should have at least 5 articles (unless it’s a temporary placeholder).

- Categories should not overlap unnecessarily. If two categories mean the same thing, one gets merged.

There’s also a “category tree” project where volunteers map out the entire structure. They’ve identified over 150,000 active categories and 800,000 category links. The goal? To make sure no topic is orphaned and no category is buried under too many layers.

And then there’s the problem of bias. Most categories reflect Western, English-language perspectives. The category European history has 12,000 articles. African history has 3,200. That’s not because Africa’s history is less important-it’s because fewer editors have contributed. Wikipedia’s taxonomy is a mirror of its community, and that’s both its strength and its weakness.

How This System Compares to Other Encyclopedias

Traditional encyclopedias like Britannica use rigid hierarchies. They group topics by subject, then by subtopic, then by article. It’s clean, but inflexible. If you want to find articles about “women in science,” you’d have to look in multiple places-physics, biology, history-because Britannica doesn’t cross-link by theme.

Wikipedia does. Its taxonomy lets you find the same article through multiple paths. Marie Curie can be found under Physicists, Chemists, Women scientists, Nobel laureates, and Polish emigrants to France. That’s not a bug-it’s a feature. It reflects how humans actually think: not in neat boxes, but in overlapping networks.

Even Google’s Knowledge Graph, which powers search results, borrows from Wikipedia’s category system. When you search for “Leonardo da Vinci,” Google pulls data from Wikipedia’s categories: Painters, Inventors, Italian Renaissance. Wikipedia didn’t build Google’s system-but it gave it its foundation.

Why This Matters

Wikipedia’s category and taxonomy system isn’t just about organization. It’s about making knowledge accessible, interconnected, and alive. It turns a collection of articles into a living network. Every category you click, every link you follow, every path you trace builds a deeper understanding-not just of one topic, but of how everything connects.

For students, researchers, and curious minds, this system is a silent teacher. It doesn’t shout. It doesn’t advertise. It just works. And that’s why, despite its flaws, it remains the most powerful knowledge organization system ever built by volunteers.

How are Wikipedia categories created?

Wikipedia categories are created by registered editors who add them manually using the syntax [[Category:Name]]. Categories must follow naming conventions-lowercase, singular, and based on encyclopedic relevance. They’re reviewed by the community to avoid duplication, bias, or unnecessary detail.

Can a Wikipedia article belong to multiple categories?

Yes, an article can belong to multiple categories. For example, the article on the iPhone is categorized under Smartphones, Apple products, Mobile phones, and 2007 introductions. This multi-path structure helps users find information from different angles.

Do Wikipedia categories affect search results?

Yes. Wikipedia’s internal search engine uses categories to improve relevance. When you search for a term, the system checks not just the article text, but also the categories it belongs to and the categories of linked articles. This helps surface the most contextually relevant results.

Why do some Wikipedia categories have thousands of articles while others have only a few?

This reflects both topic popularity and editor activity. Categories like People or United States have huge numbers because they’re broad and heavily edited. Narrower categories, like 20th-century chemists from Sweden, have fewer entries simply because fewer editors contribute to those specific areas. The system adapts to usage, not design.

How does Wikipedia handle category overlap or conflict?

Wikipedia has guidelines to prevent overlap. If two categories are too similar, editors propose a merge. If a category is too broad, it’s split. There are also category discussion pages where editors debate structure. The goal is always clarity and usefulness-not perfection.