Wikipedia isn’t just one website. It’s over 300 separate versions-each with its own editors, rules, and culture. The English version gets most of the attention, but more than half of all Wikipedia edits happen in languages other than English. In fact, the Japanese, German, French, and Russian editions each have more active editors than some small countries have people. Yet, these communities rarely talk to each other. Why? And how do they manage to build knowledge together across language barriers?

Why Language Diversity Matters on Wikipedia

Wikipedia’s mission is to give everyone free access to the sum of all human knowledge. But if only English speakers contribute, that knowledge becomes skewed. A topic like "traditional medicine in Southeast Asia" might have 50 detailed articles in Thai, but only a single paragraph in English. Meanwhile, "American football" might have dozens of pages in English, but almost nothing in Swahili or Bengali. This isn’t just imbalance-it’s distortion.

Studies from the Wikimedia Foundation show that articles in smaller language editions often contain unique local knowledge not found anywhere else. For example, the Tagalog edition has detailed entries on indigenous Philippine festivals that don’t appear in English Wikipedia at all. The same goes for the Quechua edition’s coverage of Andean agricultural practices or the Yoruba edition’s records of oral history traditions.

Without these languages, Wikipedia doesn’t represent global knowledge. It represents a narrow slice of it.

How Editors Work Across Languages

Most Wikipedia editors only work in one language. That’s normal. You’re more likely to edit about topics you understand deeply-and that usually means your native language. But collaboration still happens. It’s not always direct. It’s often indirect, through tools and shared practices.

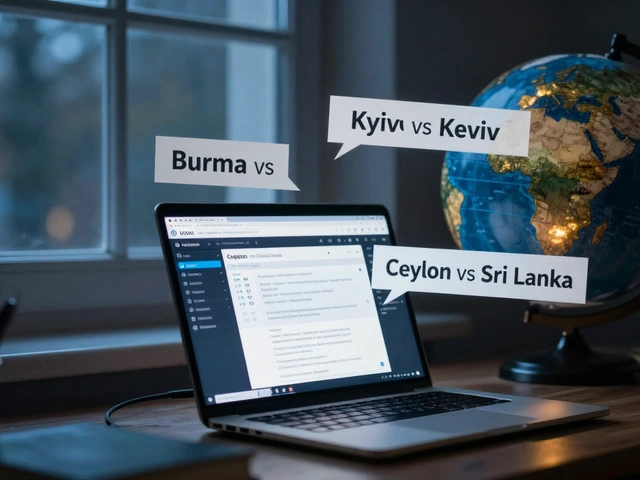

One key method is interlanguage links. These are the links you see on the bottom of articles that say "In other languages: Deutsch, Français, العربية." Editors in one language will add these links to point readers to related content in other editions. But here’s the catch: those links only get added if someone in the other language community has already written a decent article. That creates a chicken-and-egg problem. No one writes about a topic in Swahili if they can’t find a good English version to base it on.

Some communities solve this with translation tools. The Content Translation tool, developed by Wikimedia, lets editors pick an article in one language and translate it into another with built-in suggestions. It’s not perfect-machine translations often miss cultural context-but it’s helped add over 2 million articles to smaller language editions since 2015. The Bengali and Tamil editions, for instance, grew by over 30% in just three years thanks to this tool.

Then there are edit-a-thons. These are organized events where editors from different language backgrounds come together-online or in person-to work on underrepresented topics. In 2023, a global edit-a-thon focused on Indigenous languages led to 1,200 new articles in Quechua, Guarani, and Ainu. Volunteers from Spain, Brazil, and Canada worked together, using chat rooms and shared documents to coordinate. They didn’t all speak the same language, but they all spoke Wikipedia.

Barriers to Real Collaboration

Even with tools, collaboration is hard. The biggest problem isn’t technology-it’s culture.

Wikipedia’s policies are written in English and often assume a Western, individualistic approach to editing. In many cultures, consensus-building takes longer. In parts of Asia and Africa, group harmony matters more than being the first to edit. That clashes with Wikipedia’s fast-paced, edit-war-prone environment. A user in Indonesia might wait weeks to get feedback before making a change. A user in the U.S. might revert an edit within minutes.

Language differences also create power imbalances. Editors in large language communities often dominate discussions on Meta-Wiki, the central hub for global policy. When a new guideline is proposed, it’s usually debated in English. Non-native speakers struggle to keep up. Even if they understand the words, they miss the tone, sarcasm, or unspoken rules. As a result, smaller language communities feel excluded from decisions that affect them.

There’s also a lack of trust. Some editors assume that content in other languages is less reliable. They’ll cite an English article as "authoritative" while ignoring a longer, better-sourced version in Polish or Korean. This isn’t just bias-it’s systemic. It’s reinforced by how search engines rank content. Google often surfaces English results first, making them seem more legitimate, even when they’re not.

Strategies That Actually Work

Some communities have found ways around these problems. They don’t wait for top-down solutions. They build their own.

In the Arabic-speaking world, editors formed a network called "Wikimedians of the Arab World." They hold monthly video calls in Arabic, share translation guides, and create templates for common topics like family trees and local history. They don’t rely on English-language tools. They made their own.

The Korean Wikipedia community runs a "Buddy System," pairing new editors with experienced ones who speak the same language. But they also assign bilingual mentors who can help bridge to English. This isn’t about translation-it’s about teaching how Wikipedia works in a different cultural context.

Another successful model is the "Language Bridge" project, started by volunteers in India. They trained students to act as intermediaries between Hindi, Tamil, and English editors. These students didn’t edit Wikipedia themselves. Instead, they summarized key points from one language version and presented them to another group in their own language. It turned passive readers into active connectors.

These efforts work because they’re local, not global. They respect how people actually communicate, not how Wikipedia wishes they would.

What’s Missing: The Lack of Shared Infrastructure

Wikipedia’s infrastructure was built for English. The editing interface, the discussion forums, even the help pages-all assume you’re fluent in English. There’s no official multilingual chat system. No central place where an editor in Ukraine can easily find an editor in Vietnam who knows both languages and wants to help.

There’s also no standard way to track which topics are missing across languages. Someone in Brazil might spend weeks writing about a local bird species, only to find out that someone in Portugal already wrote a better version. Or worse-they never find out at all.

Some volunteers have built unofficial tools. One group created a dashboard that shows which articles exist in at least three languages but are missing in others. Another built a bot that flags when a new article in Swahili matches an English article with no interlanguage link. These aren’t official Wikimedia projects. They’re made by people who cared enough to fix the gaps themselves.

The Future: More Than Translation

The goal isn’t to make every language version a copy of the English one. That would kill diversity. The goal is to make every version a unique contribution to a global whole.

That means letting communities set their own priorities. The Māori Wikipedia doesn’t need more articles about U.S. presidents. It needs more about tribal governance, ancestral land rights, and traditional navigation. The Hausa edition doesn’t need better coverage of Hollywood. It needs better coverage of Islamic scholarship in West Africa.

Wikipedia’s future depends on whether it can become a true network of equals-not a hierarchy with English at the top. That won’t happen because of a policy change. It’ll happen because editors in Lagos, Lima, and Ljubljana decide to reach out, share, and build together.

The tools are there. The knowledge is there. What’s missing is the connection.

Why don’t more Wikipedia editors work across languages?

Most editors stick to their native language because they understand the cultural context, terminology, and sources best. Translating isn’t just about swapping words-it’s about adapting tone, references, and even what counts as "important." Many also lack the time or confidence to navigate complex discussions in a second language.

Can machine translation replace human collaboration on Wikipedia?

No. Machine translation can help draft content, but it often gets cultural references wrong, misses local nuance, or adds biased phrasing. A machine might translate "sacred tree" as "holy plant," but it won’t know that in a specific Indigenous community, that tree has ritual significance tied to seasonal cycles. Human editors bring context that algorithms can’t replicate.

Are smaller language editions less reliable than English Wikipedia?

Not necessarily. Some small-language editions have stricter sourcing rules than English Wikipedia. For example, the Icelandic edition requires citations from local archives for historical claims, while the English version often accepts secondary sources. Reliability depends on community norms, not language size. Many high-quality articles in Catalan or Vietnamese are better sourced than their English equivalents.

How can someone help improve language diversity on Wikipedia?

You don’t need to be fluent in another language to help. You can add interlanguage links to articles you edit, report missing translations, or join a global edit-a-thon. If you speak two languages, you can help translate key articles or mentor new editors. Even sharing Wikipedia content in your community can encourage others to contribute.

Does Wikipedia have plans to fix language inequality?

The Wikimedia Foundation supports language diversity through grants, translation tools, and outreach programs. But it doesn’t control how communities operate. Real change comes from editors themselves. The Foundation provides tools; local communities decide how to use them. The most effective efforts are grassroots-led by volunteers who live in the cultures they represent.