Wikipedia isn’t just a reference site-it’s a news source. Reporters, bloggers, and TV producers pull from it daily. But when the press treats Wikipedia like a primary source, things go wrong. Fast. And when they do, the mistakes don’t just disappear. They spread. And sometimes, they stick.

When the New York Times Got Wikipedia Wrong

In 2006, the New York Times ran a front-page story claiming that Wikipedia’s founders had admitted the site was unreliable. The quote came from a Wikipedia user who edited under the name "Ezra Klein"-a fake account. The real Ezra Klein, now a well-known political commentator, had never edited Wikipedia. The Times didn’t verify the username. They didn’t check the edit history. They quoted a bot pretending to be a person.

The error made headlines. Then it made memes. Then it made people distrust Wikipedia even more. The Times issued a correction three days later, buried on page A18. But by then, the damage was done. The story was cited in congressional hearings, referenced in academic papers, and used by critics to argue that online knowledge was inherently untrustworthy.

What went wrong? The reporter assumed that a Wikipedia username was a real identity. That’s a trap many journalists fall into. Wikipedia has over 60 million registered accounts. Millions are bots. Thousands are trolls. A few are real people using pseudonyms. You can’t tell the difference by looking at the name alone.

The BBC’s "Sachsgate" Debacle

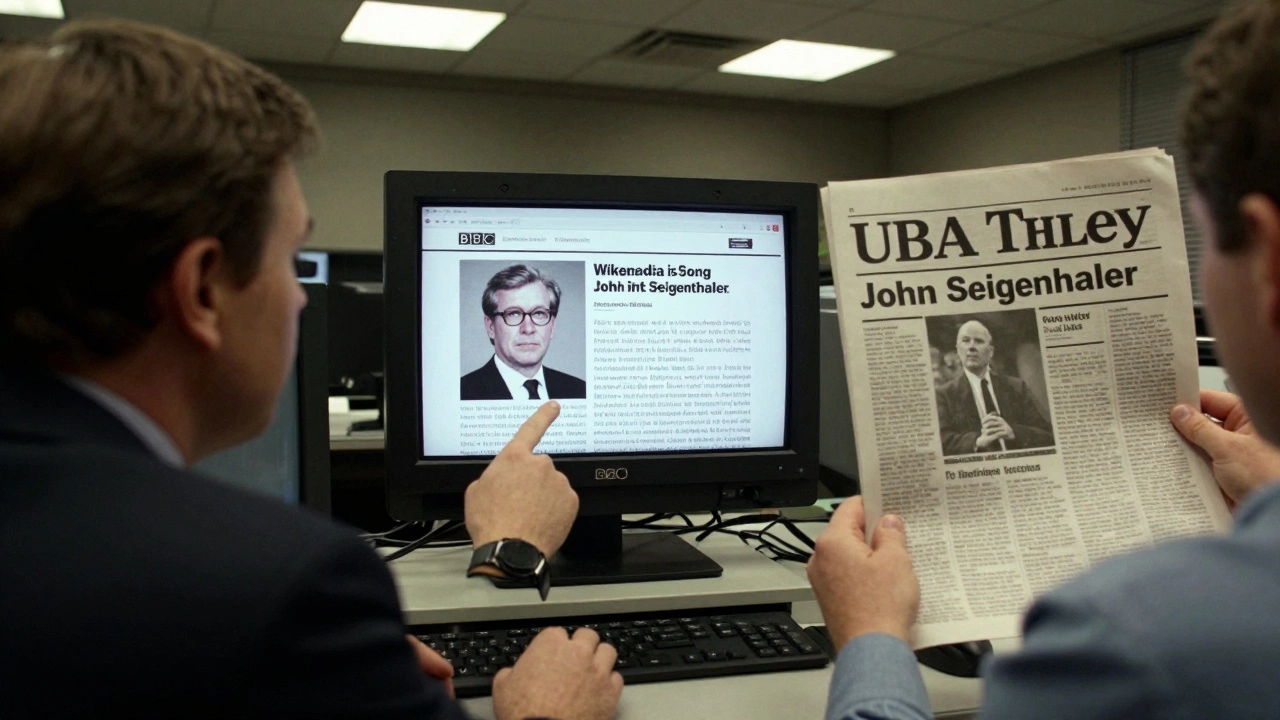

In 2005, a Wikipedia user named "Seigenthaler" created a hoax article about John Seigenthaler, a respected American journalist and former aide to Robert F. Kennedy. The fake entry claimed Seigenthaler had been a suspect in the JFK assassination. It stayed live for four months.

When Seigenthaler found out, he wrote a scathing op-ed in USA Today. The story went viral. The BBC picked it up and ran a segment titled "Wikipedia: The Truth Behind the Lies." They cited the hoax article as evidence that Wikipedia was dangerous. They didn’t mention that the article had been deleted. They didn’t say it was a known fraud. They treated a removed edit like a live fact.

The BBC later apologized. But their mistake had consequences. It fueled a narrative that Wikipedia was a breeding ground for misinformation-ignoring the fact that most hoaxes are caught quickly, and Wikipedia’s correction system is one of the most responsive in the world.

How the Guardian Got Fooled by a Troll

In 2013, the Guardian published a story about a "newly discovered" Wikipedia edit war between two U.S. senators. The article claimed one senator had inserted false biographical details into the other’s page. The details were absurd: "Senator X was born on Mars," "Senator Y once ran for president as a kangaroo."

The Guardian didn’t check the edit history. They didn’t contact either senator’s office. They didn’t notice the article had been flagged as vandalism and reverted within 12 minutes. The hoax was posted by a user named "WikipediaLover123," who had been banned from the site three times before.

The story ran. Then it got picked up by Forbes, Politico, and even a Canadian TV network. It wasn’t until a Wikipedia editor reached out to the Guardian with screenshots of the revert log that the paper pulled the article. They published a brief note: "We regret the error."

But the damage was already done. The hoax became part of the public conversation about Wikipedia’s reliability. People started quoting it as proof the site was broken.

Why the Press Keeps Making These Mistakes

There’s a pattern here. Reporters treat Wikipedia like a newspaper. They assume if it’s on the page, it’s true. They don’t dig into edit histories. They don’t check talk pages. They don’t look for citations. They see a name, a sentence, and they run with it.

Wikipedia doesn’t work like a newspaper. It’s a living document. Every edit is public. Every change is tracked. Every mistake can be undone-in minutes, sometimes seconds. But the press doesn’t see that. They see a static article. And they treat it like gospel.

Wikipedia’s own guidelines say: "Do not cite Wikipedia as a primary source." But journalists ignore it. Why? Because it’s easy. Because it’s fast. Because they’re on deadline.

And when they get it wrong, they don’t blame their own process. They blame Wikipedia.

What Journalists Should Do Instead

Wikipedia isn’t the enemy. The real problem is lazy reporting. Here’s how to use it right:

- Use Wikipedia to find sources, not to quote them. Look at the references at the bottom of an article. Track down the original book, study, or interview. Cite that.

- Check the edit history. If you’re quoting a claim, scroll to the bottom of the page and click "View history." See when it was added. Was it recent? Was it reverted? Who made the edit?

- Read the talk page. The talk page shows debates between editors. If there’s controversy around a claim, it’s usually flagged there.

- Don’t trust usernames. "DrJohnSmith" isn’t a doctor. "TruthSeeker99" isn’t a journalist. Verify identities through official channels.

- Don’t report vandalism as news. If something looks outrageous, check if it’s been removed. Most hoaxes are gone within an hour.

There are tools to help. The Wikipedia:Reliable sources page lists trusted publications. The WikiProject Journalism group flags articles that are frequently misused by media. And the Wikipedia Edit History Tool lets you see exactly who changed what and when.

The Real Lesson

Wikipedia has made over 1.2 billion edits. Most are small: fixing a typo, updating a date, adding a citation. A tiny fraction are malicious. And nearly all of them are caught.

But the press keeps treating Wikipedia like a minefield. They focus on the bombs and ignore the cleanup crew.

The real danger isn’t Wikipedia’s errors. It’s the media’s failure to understand how it works. When journalists report Wikipedia’s corrections as proof of failure, they’re missing the point. Wikipedia’s strength isn’t in being perfect. It’s in being self-correcting.

Every time a hoax is exposed, Wikipedia gets stronger. Every time a journalist learns to check the edit history, the public gets better information.

The lesson isn’t that Wikipedia is unreliable. The lesson is that the press still hasn’t learned how to use it.

What Happens When the Press Gets It Right

There are exceptions. In 2019, The Atlantic published a deep-dive on how Wikipedia handles political bias. They didn’t quote the article. They interviewed editors. They analyzed edit patterns. They showed how a neutral point of view is enforced through community consensus.

The piece didn’t go viral. But it was cited by university journalism programs. It became required reading in media ethics courses.

That’s the right way to cover Wikipedia. Not as a source. But as a system.

Wikipedia doesn’t need to be perfect. It just needs to be transparent. And the press needs to stop pretending it’s something it’s not.

Why do journalists keep citing Wikipedia as a source?

Journalists cite Wikipedia because it’s fast, free, and easy to access. Many are on tight deadlines and use it to quickly confirm basic facts like birth dates, event timelines, or definitions. But they often mistake Wikipedia’s convenience for credibility. Wikipedia itself advises against using it as a primary source, but reporters ignore that warning because they don’t know how to trace information back to original sources.

Are Wikipedia hoaxes common?

Wikipedia hoaxes are rare and usually short-lived. Most are removed within minutes or hours by automated bots or volunteer editors. The infamous John Seigenthaler hoax lasted four months, but that’s an extreme outlier. Since 2001, Wikipedia has over 60 million registered users and 1.2 billion edits. The vast majority of edits are helpful, and vandalism is detected and corrected quickly. The media tends to amplify the rare failures while ignoring the constant corrections.

Can you trust Wikipedia for breaking news?

No. Wikipedia is not designed for breaking news. It requires consensus and citations before changes are finalized, which takes time. During fast-moving events like elections or disasters, Wikipedia pages often contain outdated or unverified information. Reliable news outlets use Wikipedia to track how stories evolve, but they verify facts through primary sources like press releases, official statements, or eyewitness accounts.

How do you check if a Wikipedia edit is legitimate?

Click the "View history" tab on any Wikipedia article. Look at the edit summary, the username, and the timestamp. If the edit is recent and lacks a citation, be skeptical. Check the talk page to see if other editors are questioning the change. Use the Wikipedia Edit History Tool or tools like WikiWho to trace who made the edit and whether they have a history of vandalism. Always cross-check the claim with a cited source.

What’s the best way to use Wikipedia as a journalist?

Use Wikipedia as a starting point, not an endpoint. Read the references listed at the bottom of the article. Track down the original book, study, or interview. Contact the authors or institutions cited. Use the talk page to understand controversies around a topic. Avoid quoting Wikipedia directly unless you’ve verified the edit’s legitimacy and context. The goal isn’t to cite Wikipedia-it’s to use it to find better sources.

Wikipedia isn’t broken. The press just hasn’t learned how to use it right. Fix that, and the errors stop.