What’s in a name? On Wikipedia, it can spark months of debate, edit wars, and even international diplomatic complaints. The platform doesn’t just report facts-it decides how those facts are named. And that’s where things get messy.

Why Names Matter More Than You Think

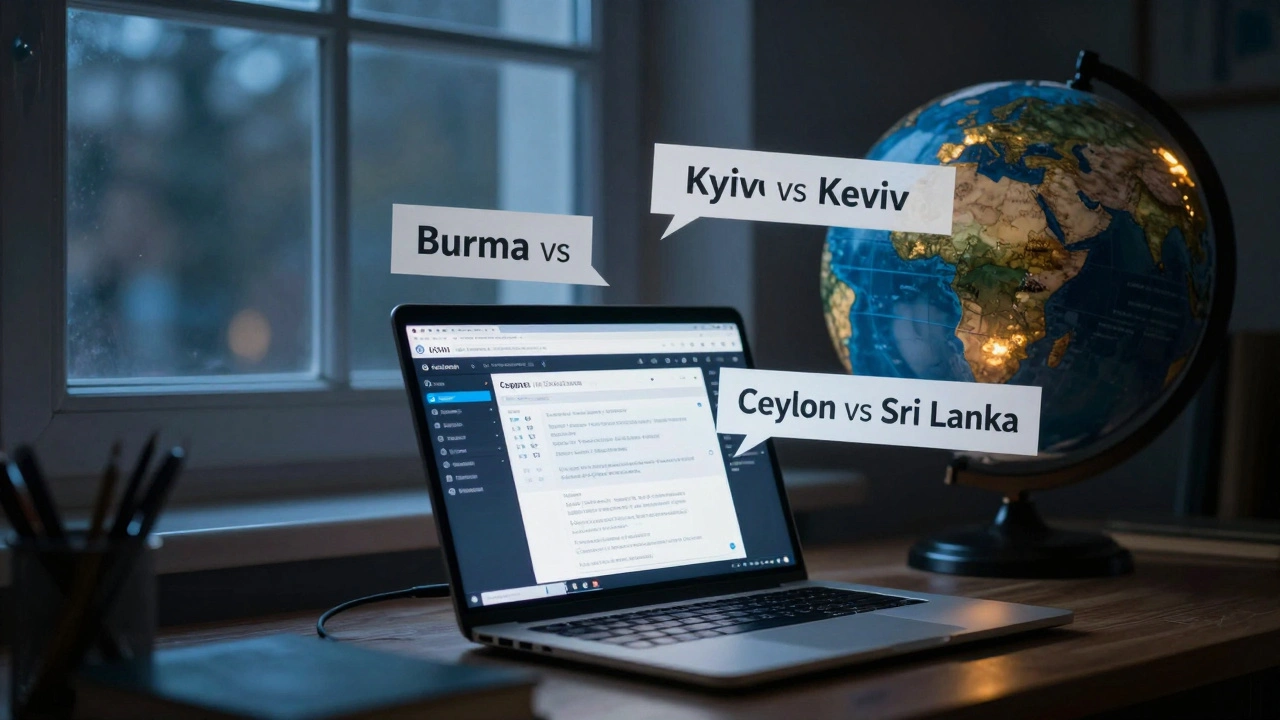

Wikipedia’s naming conventions aren’t about grammar or style. They’re about power. When you type "Kyiv" into Google, you get the Ukrainian spelling. Type "Kiev", and you get the Russian version. Wikipedia has to pick one. That choice isn’t neutral. It’s political.

In 2019, after Ukraine’s government officially pushed for "Kyiv" in English media, Wikipedia editors spent over 800 edits debating whether to change the article title. Some argued that "Kiev" was still the most common spelling in English-language publications. Others said using the Russian-derived form ignored Ukrainian sovereignty. The decision to switch wasn’t made by a single person. It was voted on by hundreds of volunteers, many of whom had never been to Ukraine.

It’s not just Ukraine. The same fight happened with "Taiwan" vs. "Taipei". "Czech Republic" vs. "Czechia". "Macedonia" vs. "North Macedonia". Each time, the stakes aren’t just about spelling-they’re about recognition, identity, and history.

The Rule That’s Supposed to Prevent Bias

Wikipedia has a policy called "Preferred Common Names". In theory, it’s simple: use the name most commonly used in reliable English-language sources. But here’s the catch-what counts as "reliable"? A British newspaper? An American textbook? A U.S. State Department document?

When the U.S. government switched from "Burma" to "Myanmar" in 1989, Wikipedia didn’t immediately follow. Why? Because many English-language sources, including the BBC and The New York Times, kept using "Burma" for years. Editors worried that switching too soon would make the article look like propaganda, not a neutral reference.

But that’s the problem. Reliance on Western media creates a feedback loop. If most English sources ignore local preferences, Wikipedia ends up reflecting colonial or imperial norms. For example, many African place names still appear in their colonial spellings on Wikipedia, even though local governments have officially changed them. The city of "Harare" in Zimbabwe was called "Salisbury" until 1982. But older articles, textbooks, and even some Wikipedia references still use the old name.

How Bias Creeps In Without Anyone Intending It

Most Wikipedia editors aren’t trying to be biased. They’re volunteers-students, retirees, librarians-who just want to make the site accurate. But they’re not from everywhere. A 2021 study by the Oxford Internet Institute found that over 70% of Wikipedia’s active English-language editors are from North America or Western Europe. That means decisions about names often come from people who’ve never lived in the places they’re naming.

Take "Sri Lanka". The country officially dropped "Ceylon" in 1972. But for years, Wikipedia’s "Ceylon" page remained a redirect to "Sri Lanka". Why? Because editors assumed anyone searching for "Ceylon" just wanted the current name. They didn’t consider that people might be looking for historical information-colonial records, old maps, genealogical research. The solution? Keep both. Create a separate historical article titled "Ceylon (1815-1972)" and link it clearly. But that takes time, awareness, and someone who knows the context.

Same with "Istanbul". The city was called "Constantinople" for over a thousand years. Turkey officially switched in 1930. But many English-language sources still use "Constantinople" when referring to the Byzantine era. Wikipedia handles this by using "Istanbul" as the main title but adding "(formerly Constantinople)" in the first sentence. That’s good practice-but it only works if someone knows to do it.

Titles of People: Gender, Royalty, and Contested Legacies

Place names aren’t the only battleground. People’s titles are too.

Should we call former U.S. President Donald Trump "President Trump" after leaving office? Wikipedia says no-only current officeholders get the title. But what about Queen Elizabeth II? She’s dead. Yet her article still says "Queen Elizabeth II". Why? Because Wikipedia treats royal titles differently-they’re part of the person’s historical identity, not just their job.

Then there’s the case of controversial figures. Should a convicted criminal be called "Dr." if they earned a PhD? Should a disgraced scientist be referred to by their academic title? Wikipedia’s policy says yes-if the title was earned and widely recognized. But editors often disagree. One editor might see "Dr." as a factual credential. Another sees it as giving legitimacy to someone who abused their position.

And what about gender? In 2023, Wikipedia updated its guidelines to allow "Mx." as a neutral honorific for living people who use it. But applying it to historical figures? That’s still hotly debated. Should we refer to the 19th-century writer George Eliot (real name Mary Ann Evans) as "Mx. Eliot"? Some say yes-it honors how she lived. Others say no-it imposes modern identity labels on the past.

How Wikipedia Handles Disputes (And Why It Sometimes Fails)

When a naming conflict arises, Wikipedia doesn’t let one editor decide. There’s a process: discussion pages, consensus votes, mediation, and sometimes arbitration.

Every article has a "Talk" tab. That’s where the real work happens. Editors post sources, argue interpretations, cite policy, and sometimes just vent. The goal is consensus-not majority rule. One person with deep knowledge of a region can sway the outcome if they present solid evidence.

But here’s the flaw: the loudest voices win. If 50 editors from the U.S. and UK all argue for "Kiev", and only 5 from Ukraine argue for "Kyiv", the former group often dominates. Language barriers, time zones, and access to reliable sources make it harder for non-Western editors to participate. And even when they do, their arguments can be dismissed as "biased" or "nationalistic"-even when they’re just citing their own government’s official stance.

Wikipedia’s own data shows this. A 2023 internal audit found that articles about countries in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia were 37% more likely to retain outdated colonial names than articles about European or North American places.

What’s Being Done to Fix It

Wikipedia isn’t ignoring the problem. In 2022, the Wikimedia Foundation launched "WikiProject Names", a global effort to improve naming accuracy across languages. Volunteers from over 40 countries now work together to update place names, verify sources, and train new editors.

Some changes are small but meaningful. The article for "Mumbai" now includes a section titled "Historical names: Bombay and other variants", with links to colonial-era maps and British records. The article for "Palestine" now includes a detailed note explaining why both "State of Palestine" and "Palestinian territories" are used in different contexts.

And in 2025, Wikipedia introduced a new feature: "Naming Suggestions". If you’re editing an article and notice a name that might be outdated, you can flag it. The system then alerts editors who specialize in that region. It’s not perfect-but it’s a step toward making the process more inclusive.

What You Can Do

You don’t need to be an expert to help. If you notice a place name that feels off-like "Peking" instead of "Beijing", or "Holland" when they mean "the Netherlands"-you can check the Talk page. Look for recent discussions. If none exist, start one. Cite a reliable source: a government website, a UN document, a major news outlet from that country.

Don’t just change it. Explain why. Say: "According to the Indonesian government’s 2020 language policy, the official spelling is 'Yogyakarta'. The Wikipedia article still uses 'Jogjakarta', which is an older variant. I’ve updated it and added a note about the change."

And if you’re from a region where names are contested? Share your knowledge. Write a short guide. Join a WikiProject. Your voice matters more than you think.

It’s Not About Perfect Accuracy-It’s About Fairness

Wikipedia will never be perfect. There will always be disagreements. But the goal isn’t to get every name right. It’s to make sure every voice has a chance to be heard.

Names are more than labels. They carry memory, resistance, dignity. When Wikipedia gets them right, it doesn’t just inform-it respects.

Why does Wikipedia use "Kyiv" instead of "Kiev"?

Wikipedia uses "Kyiv" because it’s the official spelling in Ukrainian and the form most commonly used in Ukrainian media and government documents. After 2019, major English-language sources like the BBC, The Guardian, and the U.S. State Department also adopted "Kyiv". Wikipedia’s policy requires using the most common and official name in reliable sources, not the oldest or most familiar one.

Can I change a place name on Wikipedia myself?

You can suggest a change, but you shouldn’t make it unilaterally. First, check the article’s Talk page to see if others have discussed it. If not, start a discussion with reliable sources that support the change. If there’s consensus, you can update the name. If there’s disagreement, the community will mediate the issue.

Does Wikipedia favor Western sources over local ones?

Historically, yes. Wikipedia relies on English-language sources, and many of those come from North America and Europe. This has led to outdated or colonial names persisting in articles about non-Western regions. Efforts like WikiProject Names are working to fix this by bringing in editors from underrepresented regions and prioritizing local, official sources.

Why does Wikipedia still use "Ceylon" in some places?

"Ceylon" is still used in historical contexts-for example, when discussing British colonial rule or events before 1972. Wikipedia keeps separate articles for historical names and clearly links them to current ones. The main article for the country is titled "Sri Lanka", but "Ceylon" redirects to it with a note explaining the change.

How does Wikipedia handle names that are politically sensitive, like "Palestine" or "Taiwan"?

For politically sensitive names, Wikipedia uses neutral language and explains context. The article for "Palestine" notes that it refers to the State of Palestine as recognized by over 140 UN member states, while also acknowledging the term is used differently in other contexts. For "Taiwan", the article uses "Taiwan" as the primary name, with a detailed note explaining the political dispute and the position of the People’s Republic of China. The goal is to present multiple perspectives without taking sides.