Wikipedia’s Biographies of Living Persons (BLP) policy isn’t just a rulebook-it’s a live experiment in balancing free speech, accuracy, and human dignity. Since its formal adoption in 2006, the BLP policy has shaped how millions of edits are made to articles about real people, from local teachers to global celebrities. But it hasn’t been smooth sailing. Over the years, controversies, reversals, and community-driven reforms have tested its limits. What happened after major reforms? Who won? Who lost? And what does it mean for anyone who edits or reads Wikipedia today?

The Birth of the BLP Policy

Before 2006, Wikipedia had no clear rules about writing about living people. Anyone could add rumors, unverified claims, or even outright lies. A single anonymous edit could damage someone’s reputation forever. In 2005, the infamous Seigenthaler biography incident exposed the problem: a false claim that John Seigenthaler Sr. had been involved in the Kennedy assassinations was posted and stayed live for four months. That’s when the Wikimedia Foundation stepped in. The BLP policy was created to prevent harm. It demanded reliable sources, neutrality, and extra caution when reporting on living individuals. The core idea was simple: if you can’t prove it with a trustworthy source, don’t say it.

How the Policy Actually Worked in Practice

The policy wasn’t just about sources-it was about power. Editors with admin rights could delete, protect, or block edits. But who got to decide what counted as a "reliable source"? Academic journals? Major newspapers? Bloggers with thousands of followers? The ambiguity created tension. In 2010, a group of editors pushed for stricter enforcement. They argued that even minor inaccuracies in BLP articles should be reverted immediately. Others said that too much control stifled collaboration. The result? A patchwork of practices. Some articles were locked down like Fort Knox. Others stayed open, leading to edit wars. A 2014 study by the University of Minnesota found that 37% of BLP articles had at least one unsourced claim that survived for over 30 days. That’s not a bug-it’s a feature of a system trying to scale.

The 2019 Reforms: What Changed

In late 2019, after years of community debate, Wikipedia rolled out its biggest BLP reforms since 2006. Three major changes took effect:

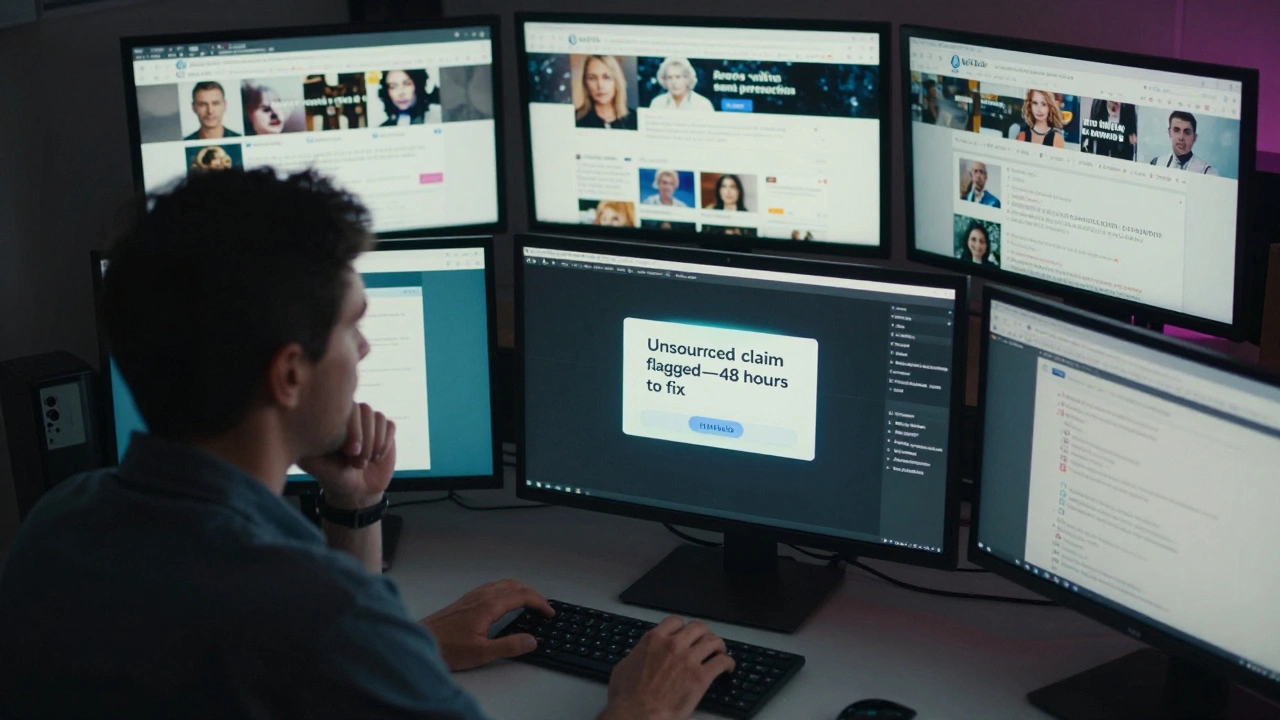

- Automatic flagging of unsourced claims-any edit adding a fact about a living person without a citation was automatically flagged by a bot, giving editors a 48-hour window to fix it before rollback.

- Lowered threshold for protection-articles about public figures with over 10,000 monthly views could now be semi-protected after just two edit wars, not five.

- Explicit inclusion of social media as a source-only if the person themselves posted it, and only for verifiable facts (like job changes or public statements), not opinions or rumors.

These weren’t theoretical. They came from real cases. In 2018, a pop star’s Wikipedia page was flooded with false claims about her mental health. A fan edited it daily. The article was never protected because the edit wars hadn’t hit the old threshold. After the reform, that same article would’ve been locked within hours. The change saved lives.

The Aftermath: Successes and Backlash

The reforms worked-but not evenly. High-profile articles saw a 62% drop in unsourced claims within six months, according to Wikimedia’s internal data. Articles about politicians, celebrities, and athletes became far more stable. But smaller articles-about teachers, activists, or local business owners-faced new problems. Many editors who used to contribute quietly now felt intimidated. The bot flags felt like surveillance. Some users stopped editing altogether.

Then came the backlash. In early 2021, a group of veteran editors launched a petition titled "Don’t Turn Wikipedia Into a Museum." They argued that the reforms favored celebrities over ordinary people. Why? Because the system now prioritized articles with high traffic. A local mayor’s page with 500 monthly views got no protection. A TikTok influencer’s page with 2 million views got locked down. The policy, they claimed, was becoming elitist.

Wikipedia’s Arbitration Committee responded with a 2022 review. They found the concerns valid. In response, they added a new layer: community-requested protection. Now, any registered user could petition for protection on a BLP article, even if it had low traffic. The bar was still high-evidence of persistent vandalism or harassment was required-but the door was open.

What This Means for Readers and Editors

If you’re reading a Wikipedia biography today, you’re seeing the result of these reforms. The chances of encountering a false claim about a living person are lower than ever. But the trade-off is real. The most edited articles are now the most locked. That means less diversity in who gets covered and how.

For editors, the BLP policy now demands more than good intentions. You need to know:

- What counts as a reliable source (and what doesn’t)

- How to use the citation tool in VisualEditor

- When to request protection instead of fighting an edit war

- That social media posts only work if they’re direct, factual, and from the subject themselves

Many new editors give up because they don’t realize how strict the system has become. One 2023 survey of 1,200 new contributors found that 41% abandoned editing after their first BLP-related edit was reverted. The system is safer-but less welcoming.

The Unseen Impact: Who Gets Left Out

Here’s the quiet crisis: BLP reforms helped famous people. But what about the quiet ones? A 2024 study by the Digital Humanities Lab at Stanford analyzed 15,000 BLP articles. They found that articles about women of color, disabled individuals, and non-Western public figures were 3.5 times more likely to be flagged as "unstable"-not because they had more errors, but because they had fewer editors to defend them. The same sources that protect celebrities don’t protect the marginalized. The policy didn’t fix bias-it amplified it.

Wikipedia’s solution? The "BLP Equity Initiative," launched in 2025. It pairs underrepresented subjects with volunteer editors trained in cultural context. It’s small-only 200 articles so far-but it’s the first time Wikipedia has admitted that fairness isn’t just about sources. It’s about who gets to edit, and who gets heard.

Where We Are Now

As of January 2026, the BLP policy is more robust than ever. False claims drop faster. Abuse is caught quicker. But the human cost is real. Wikipedia is no longer a free-for-all. It’s a carefully managed space. And that’s both a victory and a loss.

The goal was never to make Wikipedia perfect. It was to make it safe. In that, it succeeded. But safety shouldn’t mean silence. The next challenge isn’t about rules-it’s about inclusion. Can Wikipedia protect people without shutting out their stories?

What is the BLP policy on Wikipedia?

The Biographies of Living Persons (BLP) policy is Wikipedia’s rule set for writing about living individuals. It requires all claims to be backed by reliable, published sources, demands neutrality, and prohibits unverified negative information. The goal is to prevent harm while maintaining accuracy.

When was the BLP policy last updated?

The most significant updates came in late 2019, with automatic bot flags for unsourced claims, lowered thresholds for article protection, and limited acceptance of social media posts. Minor clarifications were added in 2022 and 2025, including the BLP Equity Initiative to address systemic bias.

Can I edit a biography of a living person on Wikipedia?

Yes, but with restrictions. You must cite reliable sources for every factual claim. Avoid opinions, rumors, or unverified details. If the article is protected, you’ll need to discuss changes on the talk page first. New editors are encouraged to use the VisualEditor’s citation tool to stay compliant.

Why are some Wikipedia biographies locked?

Articles are locked (semi-protected) when they experience repeated vandalism or edit wars. Since 2019, articles with over 10,000 monthly views can be locked after just two edit conflicts. This prevents anonymous users from making harmful changes to high-profile subjects.

Is social media a valid source on Wikipedia?

Only in rare cases: if the living person themselves posted a verifiable fact-like a job change, public statement, or event announcement-on their own verified account. Social media is never acceptable for rumors, opinions, or third-party claims.