Wikipedia doesn’t run on algorithms or ads. It runs on people. Specifically, on a shrinking group of dedicated editors who show up day after day to fix typos, cite sources, and argue over punctuation in the talk pages. But who are these people? And why do so many of them quit?

In 2025, Wikipedia had fewer than 70,000 active editors monthly-down from over 500,000 at its peak in 2007. That’s not a glitch. It’s a systemic collapse. And the platform knows it. So it’s trying to fix itself-not with more bots, not with better UIs, but with human connections: mentorship, the Teahouse, and growth features designed to help new editors stick around.

Why Editors Leave

Most people think Wikipedia editors are just nerds with too much free time. But the reality is more complicated. The average editor is a 32-year-old man from a Western country, with a college degree and tech familiarity. Women make up just 15-20% of active editors. People of color, non-English speakers, and older adults are even rarer.

Why? Because the culture is hostile. New editors get reverted without explanation. Their edits are tagged with cryptic templates like “WP:NOT” or “Citation needed.” They’re told to “read the guidelines” as if those 10,000-page policy docs were a user manual. No one says hello. No one offers help. Many quit after one bad experience.

A 2023 study from the University of Michigan tracked 12,000 new editors. Of those, 68% made only one edit and vanished. The ones who stayed? They had someone who said, “Hey, nice job on that reference,” or “Here’s how to fix that citation.” Simple stuff. But it made all the difference.

Mentorship: The Quiet Lifeline

Wikipedia’s formal mentorship program launched in 2019. It’s not flashy. No badges. No leaderboards. Just a matching system: experienced editors volunteer to guide newcomers for 30 days. They answer questions. They review edits. They explain why a certain template matters or how to navigate the conflict resolution process.

The results? Mentored editors were 3.4 times more likely to make 10 or more edits in their first month. They were also 50% less likely to be blocked or receive hostile replies. One mentor in Germany told me, “I don’t teach them Wikipedia. I teach them how to not feel alone here.”

But here’s the catch: only 2% of active editors sign up as mentors. Why? Because it’s invisible work. No one sees it. No one praises it. The system doesn’t reward it. And without recognition, the program stays small. It’s a lifeline-but only a few are throwing the rope.

The Teahouse: Where Newcomers Get Welcome

Enter the Teahouse. Launched in 2012 by a group of volunteers tired of seeing new editors get crushed by the system, the Teahouse is a chat space on English Wikipedia. It’s not a policy page. It’s not a help forum. It’s a place where you can ask, “What does ‘notability’ mean?” without being told to read 17 pages.

The Teahouse has 12 regular volunteers who rotate shifts. They respond in plain language. They use emojis. They laugh. They say “you got this.” And it works. A 2024 analysis of 8,000 Teahouse users showed that 61% of them became regular editors-making at least five edits per month for over six months. That’s nearly triple the retention rate of non-Teahouse newcomers.

What makes it different? It’s human. It’s casual. It’s not about rules. It’s about belonging. One user, a 68-year-old retired teacher from Ohio, said, “I thought Wikipedia was for college kids. Then I typed a question into the Teahouse. Someone replied within 12 minutes. They called me ‘sweetheart.’ I cried. I’ve edited every day since.”

The Teahouse now has sister projects in Spanish, French, and Japanese. But the English version remains the most active. And it’s the only one with a live chat window that looks like a cozy kitchen-complete with cartoon teacups and a “help yourself” sign.

Growth Features: The Engine Behind the Scenes

While mentorship and the Teahouse help emotionally, Wikipedia’s engineering team built something more mechanical: Growth Features. These are a suite of tools designed to nudge new editors toward success without overwhelming them.

Here’s what they do:

- Personalized onboarding: When you sign up, you’re asked what topics you care about. Then you get a list of 3-5 simple tasks: “Add a citation to this article about dogs,” or “Fix the date in this biography.”

- Suggested edits: The system highlights articles that need minor fixes-grammar, formatting, missing links. You click, you fix, you save. Done in under a minute.

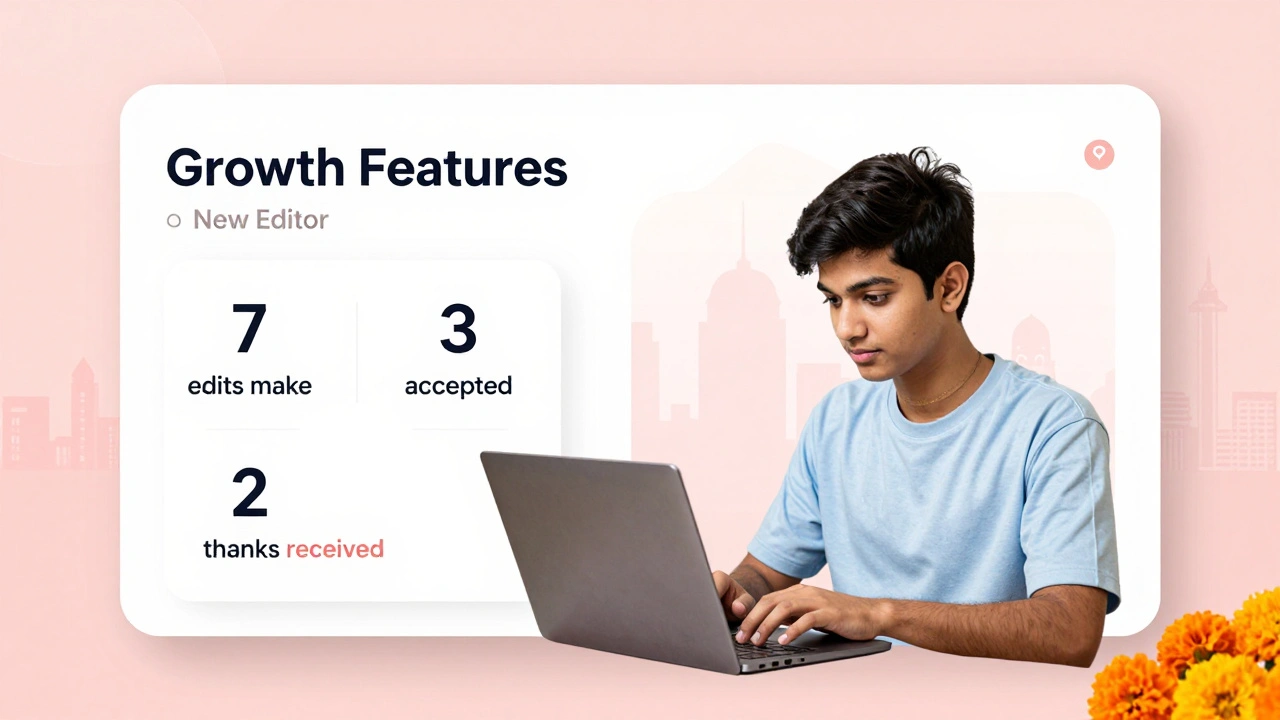

- Newcomer task feed: A dashboard that shows your progress: “You’ve made 7 edits. 3 were accepted. 2 people thanked you.”

- Help panel: A floating sidebar that pops up when you’re editing. It says: “Stuck? Ask a mentor.” Or: “Need a citation? Here’s how.”

Since rolling out Growth Features in 2020, new editor retention increased by 42% in test wikis. In countries like India and Nigeria, where internet access is growing but Wikipedia literacy is low, the impact was even bigger. One Indian user, a 19-year-old student from Mumbai, said, “I didn’t know how to cite a book. The system showed me. I did it. Then someone said ‘good job.’ I felt like I belonged.”

These tools aren’t perfect. Some veterans complain they’re “dumbing down” Wikipedia. But the data doesn’t lie: if you want more editors, you have to make editing feel possible-not intimidating.

The Demographics Are Changing-Slowly

Because of these efforts, editor demographics are shifting. In 2025, women made up 24% of new editors on wikis using Growth Features. In the Teahouse, 30% of new users were over 50. Non-English speakers using localized onboarding were 4x more likely to stick around.

It’s not a revolution. But it’s a tide. And it’s happening because Wikipedia stopped treating new editors like intruders and started treating them like guests.

What’s Still Broken

None of this fixes the deeper problems. The culture of hostility still exists in high-traffic articles. The backlog of unreviewed edits is over 2 million. The policies are still written in legalese. And most mentors still work alone, with no institutional support.

Wikipedia’s leadership still doesn’t fund these programs properly. Mentorship is volunteer-only. The Teahouse runs on goodwill. Growth Features are still limited to a few language versions.

Until the Wikimedia Foundation treats editor retention like a core product-not a side project-these efforts will remain fragile. But they’re proof that change is possible.

What You Can Do

If you’ve ever edited Wikipedia and felt welcome-you can be the reason someone else stays. You don’t need to be an expert. Just reply to a new user’s question. Say thank you. Point them to the Teahouse. Click “thank” on their edit. That’s it.

Wikipedia doesn’t need more rules. It needs more kindness.

Why do so many new Wikipedia editors quit after their first edit?

Many new editors quit because they face hostile or confusing feedback-edits are reverted without explanation, they’re told to "read the guidelines" without help, and they receive no encouragement. A 2023 study found 68% of new editors made only one edit before leaving. The lack of human connection and clear guidance makes Wikipedia feel unwelcoming, especially for people unfamiliar with its complex policies.

How does the Teahouse improve editor retention?

The Teahouse is a friendly, informal chat space where new editors can ask questions without fear of judgment. Volunteers respond in plain language, use emojis, and offer encouragement. Studies show that 61% of Teahouse users become regular editors, compared to under 20% of those who don’t use it. The key is emotional support: users report feeling seen, heard, and welcomed-something rarely offered elsewhere on Wikipedia.

What are Wikipedia’s Growth Features, and how do they help new editors?

Growth Features are a set of automated tools designed to guide new editors with low-friction tasks: suggested edits, personalized onboarding, a help panel, and a progress dashboard. These tools reduce intimidation by breaking editing into small, achievable steps. Since their rollout in 2020, retention rates for new editors increased by 42% in test wikis, especially among non-native English speakers and younger users.

Is mentorship effective on Wikipedia?

Yes-editors who are paired with a mentor are 3.4 times more likely to make 10 or more edits in their first month. They’re also half as likely to be blocked or receive hostile replies. Mentorship works because it replaces isolation with human connection. But only 2% of active editors volunteer as mentors, making the program small and underfunded despite its proven impact.

Are Wikipedia’s editor demographics changing because of these retention efforts?

Yes. In wikis using Growth Features and the Teahouse, women now make up 24% of new editors (up from 15% in 2020), and users over 50 account for 30% of Teahouse newcomers. Non-English speakers using localized onboarding are four times more likely to stay. These tools are slowly making Wikipedia less dominated by young, Western, male editors-but progress remains uneven and under-resourced.