Wikipedia runs on more than just volunteers and good intentions. It’s powered by a complex web of servers, databases, and software that most people never think about-until something breaks. When a page loads slowly, or an edit vanishes, or the site goes dark for a few minutes, that’s when people notice. But explaining how Wikipedia actually works? That’s where most journalists stumble. They talk about "crowdsourcing" or "open editing," but they skip the real engine: the technical backbone that keeps 20 billion page views a month from collapsing.

Start with the database, not the editor

Most science journalists begin with the human side: "Thousands of people edit Wikipedia every day." That’s true. But it’s misleading if you don’t follow up with: Wikipedia doesn’t store edits like a Google Doc. It uses MediaWiki, a custom-built open-source platform, and stores every change in a MySQL database. Every edit, every rollback, every username change is recorded as a row in a table called revision. That’s over 1.5 billion rows-and growing. Journalists who skip this part make Wikipedia sound like a wiki you can open in your browser. It’s not. It’s a high-traffic, distributed database system that handles more writes per second than most Fortune 500 companies.Explain the difference between the front end and the back end

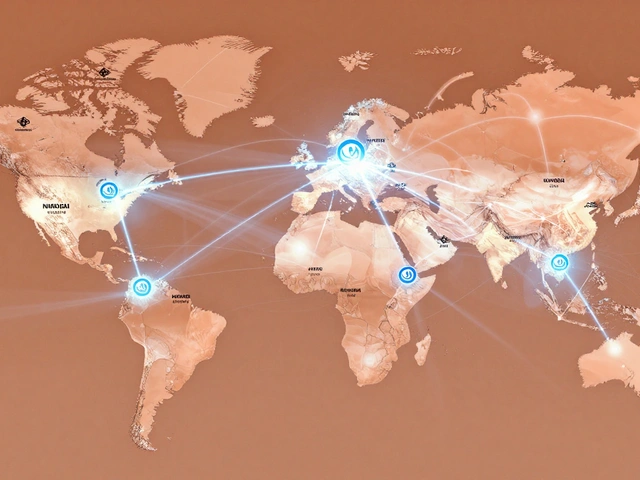

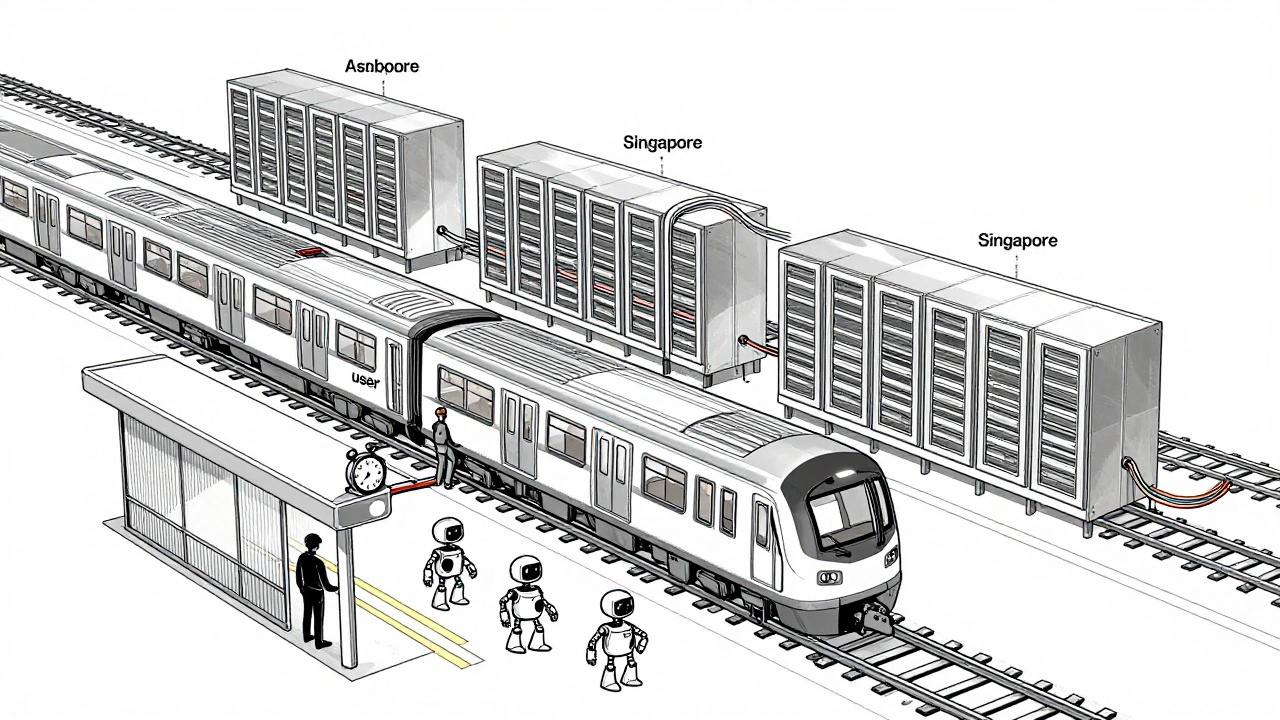

When you type "quantum computing" into your browser, you’re not talking to the people who wrote the article. You’re talking to a server in Ashburn, Virginia, or Singapore, running Apache and PHP, pulling cached data from a content delivery network. The article you see? It’s been pre-rendered and stored in memory. The real editing happens behind the scenes, in a queue. When someone clicks "Save," their edit doesn’t go live instantly. It hits a job queue, gets checked for spam, flagged for vandalism, then written to the database. Only then does it get pushed to the cache. If you don’t explain this delay, readers think Wikipedia is live-editing like a shared document. It’s not. It’s a carefully orchestrated system designed to handle millions of edits without crashing.Use analogies that don’t mislead

Avoid comparing Wikipedia to a library or a town hall. Those are too vague. Better analogies: think of Wikipedia’s infrastructure like a subway system. The trains are the servers. The tracks are the network cables. The stations are the data centers. The ticket system? That’s the authentication layer. The schedule? The caching system. If one train breaks down, others reroute. If a station gets too crowded, they open another one. This isn’t just poetic-it’s accurate. Wikimedia operates 14 data centers across four continents. Traffic flows through them based on load, latency, and redundancy. When a user in Tokyo accesses Wikipedia, they’re not connecting to a server in San Francisco. They’re connecting to the closest one with available capacity. That’s not magic. That’s engineering.

Don’t ignore the bots

About 10% of all edits on Wikipedia come from bots. Not trolls. Not humans. Automated scripts. Some fix grammar. Some revert vandalism. Some add categories. One bot, ClueBot NG, detects vandalism with 99% accuracy and reverts it in under 30 seconds. Journalists often treat bots like ghosts-mention them in passing, then move on. But bots are the unsung heroes of Wikipedia’s stability. They’re the reason the site doesn’t descend into chaos every time a troll shows up. They run on Python scripts, scheduled via cron jobs, monitored by human admins. Explaining how bots work isn’t just technical-it’s essential. Without them, Wikipedia would be unreadable.Clarify the difference between content and code

Many articles confuse the content of Wikipedia (the articles) with the code that runs it (MediaWiki). They’re not the same. The article on climate change is written in wikitext. The software that turns that wikitext into a webpage is written in PHP, JavaScript, and Lua. The templates, the infoboxes, the citation systems-all of those are code. When a journalist says, "Wikipedia’s articles are written by volunteers," they’re right. But they’re leaving out the fact that the structure those articles live in? Built by a small team of developers, most of them unpaid, working on GitHub. That’s the real story: a global encyclopedia maintained by volunteers, running on software maintained by a handful of engineers.Address the myth of "anyone can edit"

Yes, anyone can edit. But that’s not the whole truth. Wikipedia has layers of protection. New users can’t move pages. New users can’t upload files. New users can’t edit semi-protected pages. High-traffic articles like "United States" or "COVID-19" are protected by semi-protection or full protection. Editors need to be autoconfirmed-meaning they’ve made at least 10 edits and been around for four days-before they can edit certain pages. This isn’t censorship. It’s damage control. And it’s all automated. The system doesn’t rely on humans to police everything. It uses filters, flags, and blocks based on behavior patterns. Journalists who paint Wikipedia as a wild west of editing are wrong. It’s more like a gated community with security cameras and automated alarms.