When you read a scientific paper, you’re not just getting facts-you’re getting a story that’s been tested by other scientists. That’s the peer review process in action. It’s not a perfect system, but it’s the closest thing science has to a quality control check. Without it, bad ideas, sloppy data, and outright fraud would flood the literature. And that’s not hypothetical-there are real cases where papers slipped through without review and caused real harm.

What Peer Review Actually Means

Peer review is when scientists who are experts in the same field as the author review a research paper before it gets published. These reviewers aren’t hired by the journal-they’re usually volunteers, other researchers who are busy with their own work. They read the paper carefully, check the methods, look for flaws in the logic, and ask if the results actually support the claims. They might suggest changes, ask for more data, or even recommend rejection.

This isn’t just about catching mistakes. It’s about making sure the science is reproducible. If another scientist can’t repeat the experiment and get the same result, the paper doesn’t hold up. Peer reviewers often ask: "Can this be trusted?" Not just "Is this interesting?"

Most journals use what’s called "single-blind" review: the reviewers know who the authors are, but the authors don’t know who reviewed them. Some journals now use "double-blind" review, where both sides stay anonymous. That’s meant to reduce bias-like when a reviewer might be jealous of a rival’s work or dismiss a paper because it challenges their own theory.

How It Works Step by Step

Here’s how the process usually plays out:

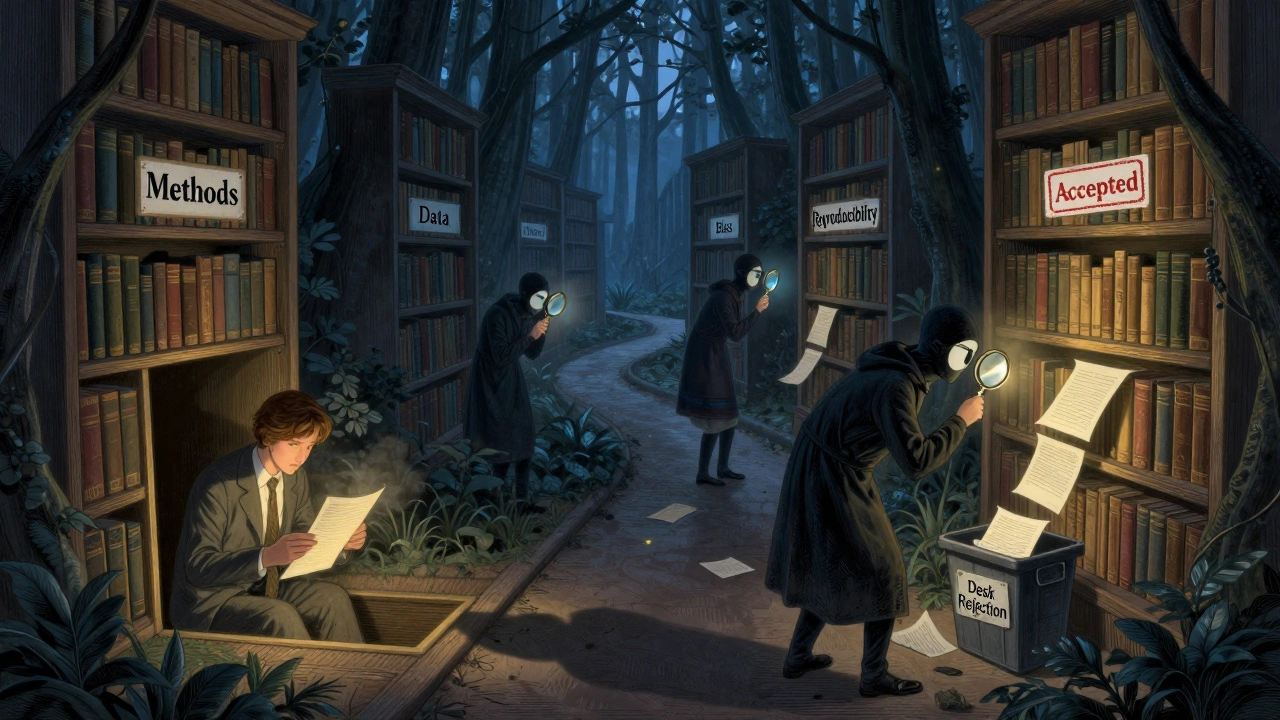

- A researcher submits a paper to a journal.

- The journal editor checks if it fits the scope and meets basic standards. If not, it gets rejected right away-this is called "desk rejection." About 30% of submissions don’t even make it past this step.

- If it passes, the editor picks two or three reviewers who are experts in that exact area. These people are chosen because they’ve published similar work, not because they’re friends with the author.

- Reviewers get 2-6 weeks to read the paper and write detailed feedback. They don’t get paid. Many do it because they believe in the system, or because they’ll be reviewed themselves someday.

- Reviewers send back comments. Sometimes they say "accept," but that’s rare. More often, they say "revise and resubmit."

- The author makes changes, sometimes major ones, and resubmits. This can take months.

- The paper goes back to reviewers, sometimes the same ones, sometimes new ones.

- After one or two rounds of revision, the editor decides: accept, reject, or revise again.

On average, a paper goes through 2-3 rounds of review before being accepted. Some take over a year. That’s not a flaw-it’s the system working. It’s slow because quality takes time.

Why It’s Not Perfect

Peer review isn’t magic. It doesn’t catch everything. A 2019 study in Nature found that reviewers missed serious statistical errors in about 1 in 5 papers they approved. Fraudulent data? Often slips through unless someone specifically looks for it.

Reviewers are human. They’re tired. They’re overworked. Sometimes they miss things. Sometimes they’re biased. A 2021 analysis showed that papers from women and researchers in low-income countries are rejected more often-even when the science is just as strong.

And then there’s the "file drawer problem"-studies that don’t show exciting results often never get published. That skews what we think we know. If 10 studies try to prove a drug works and only one says yes, that one gets published. The other nine? Buried. Peer review doesn’t fix that.

What Happens After Publication?

Peer review doesn’t end when a paper is published. In fact, that’s when real community quality assurance begins.

After publication, other scientists read the paper, try to replicate the findings, and sometimes point out mistakes. This is called "post-publication peer review." Platforms like PubPeer let researchers comment publicly on published papers. In 2023, a paper in Cell was retracted after readers on PubPeer noticed manipulated images. That wouldn’t have happened without the community watching.

Preprint servers like bioRxiv and arXiv have changed the game. Scientists now post their papers online before peer review. This speeds up sharing, but it also means readers have to judge quality themselves. That’s why peer review still matters-it’s the official stamp of scrutiny.

Who Pays for This?

Here’s the strange part: authors pay to publish. Journals charge article processing fees-sometimes over $5,000. Reviewers? They work for free. Editors? Often unpaid too. Universities and libraries pay subscription fees to access journals. The whole system is built on volunteer labor.

That’s why open access journals are growing. They let anyone read the papers for free. But they still rely on peer review. The process hasn’t changed-just who pays.

What’s the Alternative?

Some people argue we should scrap peer review and rely on post-publication feedback alone. Others say we need AI tools to scan papers for errors before humans even look. But AI can’t judge context. It can’t spot if a study’s sample size is too small or if the statistics were cherry-picked.

Human reviewers still win here. They ask: "Does this make sense?" Not just "Is this statistically significant?"

Peer review isn’t about perfection. It’s about layers of scrutiny. One scientist checks the methods. Another checks the data. A third checks the interpretation. And then, after publication, dozens more read it, question it, and build on it.

That’s community quality assurance. It’s messy. It’s slow. But it’s the best system we have.

What You Can Do

If you’re not a scientist, you still benefit from peer review. Every medical guideline, every vaccine study, every climate model you hear about? It passed through this process.

When you read a headline like "New Study Shows Coffee Prevents Cancer," ask: "Was this peer-reviewed?" If it was just a press release or a blog post, treat it with caution. Peer-reviewed science doesn’t guarantee truth-but it guarantees someone tried to break it first.

Is peer review the same as editing?

No. Editing checks grammar, clarity, and structure. Peer review checks scientific validity-whether the methods are sound, the data supports the conclusions, and the study adds real value. A paper can be perfectly written and still be rejected because the science is flawed.

Can peer review be gamed?

Yes. Some authors submit to journals where they know the reviewers personally, or they fake reviewer identities. There have been cases where researchers created fake email addresses to pose as reviewers and recommend their own papers. Journals now use tools to detect suspicious emails and conflict of interest, but it’s still a problem.

Why do some papers get rejected after years of work?

Because peer review isn’t about how hard you worked-it’s about whether the science holds up. A study might have great data, but if the sample size is too small, the control group is flawed, or the analysis is wrong, reviewers will ask for changes. If the author can’t fix it, the paper gets rejected. That’s hard, but it protects science from false claims.

Do all journals use peer review?

Most reputable journals do. But there are predatory journals-fake publishers that charge authors money and skip peer review entirely. They’ll accept almost anything. Always check if a journal is listed in directories like DOAJ (Directory of Open Access Journals) or indexed in PubMed. If it’s not, be skeptical.

How long does peer review usually take?

It varies. For top journals, the first round can take 2-6 months. After revisions, another 1-3 months. Some papers take over a year. But faster doesn’t mean better. The goal is not speed-it’s accuracy.