Most academics and teachers don’t realize how much free, high-quality material is sitting right in front of them-no paywalls, no login, no copyright headaches. Wikimedia Commons isn’t just a backup for Wikipedia images. It’s a living archive of over 100 million freely usable files: photos, audio clips, diagrams, maps, videos, and scanned documents, all vetted for legal reuse. For researchers and educators, it’s not just convenient-it’s transformative.

What Is Wikimedia Commons, Really?

Wikimedia Commons is a media repository run by the Wikimedia Foundation, the same group behind Wikipedia. But unlike Wikipedia, which is text-only, Commons holds media files that can be reused anywhere, even in textbooks, journal articles, or classroom slides. Every file is tagged with its license, source, and creator. That means you can legally use a 19th-century botanical illustration in your lecture, or a NASA photo of Mars in your student project, without asking permission or paying a fee.

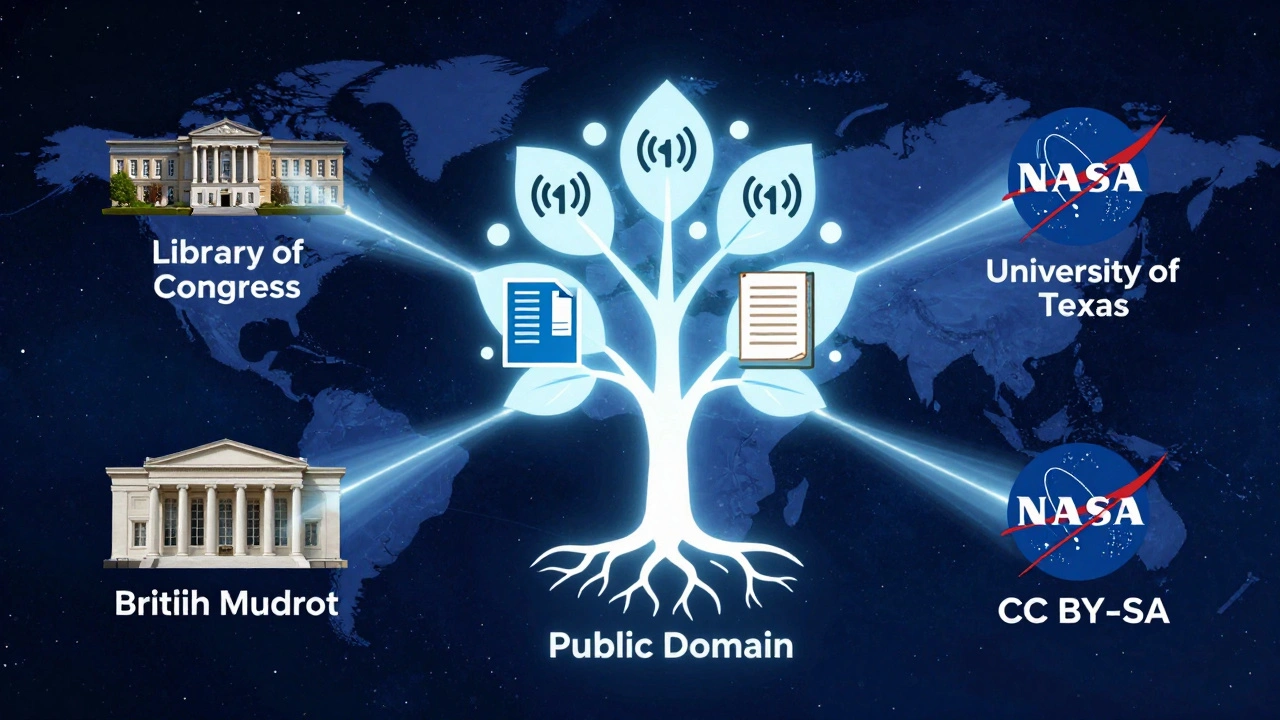

The files aren’t just random uploads. They’re curated. Contributors include museums, universities, government agencies, and citizen archivists. The Library of Congress, the British Museum, and NASA all upload directly. So when you find a photo of a Civil War soldier or a medieval manuscript, it’s often from an authoritative source, not just someone’s phone gallery.

Why It Beats Stock Photo Sites

Think you need Shutterstock or Getty Images for academic work? Think again. Stock sites charge hundreds of dollars for a single image-even if you’re teaching at a public university. Many also restrict use in educational publications or require attribution that’s too bulky for a slide deck.

Wikimedia Commons doesn’t have those limits. Most files are under public domain or Creative Commons licenses that allow free use, even commercially. You don’t need to buy a license. You don’t need to fill out a form. Just download, cite the source, and move on.

For example, a biology professor teaching plant anatomy can pull high-res scans of Linnaeus’s original botanical drawings from the Biodiversity Heritage Library-uploaded to Commons by a university library. No fee. No copyright risk. Just pure academic value.

How to Find What You Need

Searching Commons isn’t like Googling. You need to be specific. Here’s how to get better results:

- Use precise keywords: Instead of "old map," try "1850s topographic map of Wisconsin."

- Filter by file type: Click "Media type" to show only images, audio, or PDFs.

- Check the license: Look for "Public domain," "CC0," or "CC BY-SA 4.0"-these are safe for teaching.

- Look for uploads from institutions: Files from "Library of Congress," "Wellcome Collection," or "NASA" are usually reliable.

- Use the "Categories" sidebar: Browse by topic like "History of Medicine" or "Archaeological Sites in Peru."

Pro tip: If you’re looking for something obscure, try searching the same term on Wikipedia first. Often, the image used there is linked directly to its Commons page. Click the image, then click "More details" to go to the original file.

Using Commons in the Classroom

Students don’t need fancy software to create compelling projects. With Commons, you can turn a history assignment into a multimedia experience.

Here’s how one high school teacher in Ohio uses it:

- Students pick a historical event from the 1920s.

- They search Commons for photos, newspaper clippings, or audio recordings from that year.

- They build a digital exhibit using Google Slides, embedding the files directly.

- They cite each file using the attribution provided on Commons.

No one paid for images. No one broke copyright rules. The students learned how to evaluate sources, cite properly, and work with primary materials-all without a budget.

Even college-level research benefits. A grad student studying colonial architecture in Mexico can use scanned blueprints from the University of Texas’s Benson Latin American Collection, uploaded to Commons. They’re not just illustrations-they’re evidence.

Legal Clarity: What You Can and Can’t Do

Not every file on Commons is free to use however you want. Always check the license. Here’s what you need to know:

- Public domain (PD): No restrictions. You can modify, sell, or redistribute. These are often old works (pre-1928 in the U.S.) or government materials.

- CC0: The creator waived all rights. Same as public domain.

- CC BY: You must credit the creator. Easy to do-just copy the attribution text from the file page.

- CC BY-SA: You must credit the creator AND share any derivative work under the same license. Common in educational use.

- Other licenses: Some files have restrictions like "non-commercial only" or "no derivatives." Avoid these unless you’re sure they fit your use.

Never assume a file is free just because it’s on Commons. Always read the license. If in doubt, skip it. The risk of copyright claims isn’t worth it-even for teaching.

Contributing Back

Using Commons is great. But the real power comes when you give back. If you’ve digitized old family letters, scanned local archives, or taken photos of historical sites, upload them.

Here’s how to contribute:

- Make sure your files are your own work or clearly in the public domain.

- Use clear, descriptive titles and categories.

- Add a license-preferably CC0 or CC BY.

- Include location, date, and context in the description.

A professor in Wisconsin uploaded scanned pages from a 1912 school ledger from her town. Within months, researchers in Minnesota and Illinois used it to study rural education patterns. That’s the ripple effect.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even experienced users make mistakes. Here are the most common ones:

- Using a file without checking the license: Always click through to the file page. Don’t rely on the thumbnail.

- Assuming all Wikipedia images are free: Some are used under fair use and can’t be reused elsewhere.

- Ignoring metadata: The date, location, and creator info help you verify authenticity. Don’t skip it.

- Uploading low-quality scans: If your photo is blurry or cropped poorly, it won’t help anyone. Use good lighting and resolution.

- Not citing properly: Even public domain files should be cited. It’s academic integrity.

One university library in Oregon lost a grant application because a student used a photo labeled "free" on Wikipedia-but it was actually under a non-commercial license. The mistake was caught during review. It could’ve been avoided with a 30-second check on Commons.

Real Examples You Can Use Today

Here are five actual files you can start using right now:

- NASA Apollo 11 Lunar Lander - Public domain. Perfect for physics or space history lessons.

- Gutenberg Bible, page 1 - Public domain. Great for literature or printing history.

- 1918 Flu Pandemic Map - Public domain. Useful for public health or epidemiology classes.

- Marie Curie in her lab - CC BY-SA. Ideal for science biographies.

- Pueblo dwellings, 1900 - Public domain. Valuable for anthropology or Native studies.

Each link takes you directly to the file page. Download, cite, and use. No permission needed.

What Comes Next?

Wikimedia Commons is growing. More universities are partnering with it. In 2024, the University of California system launched a project to upload 50,000 digitized artifacts from its museums. The British Library has added over 1 million public domain texts. The scale is becoming impossible to ignore.

If you’re teaching or researching, you’re already using digital sources. Why not use ones that are free, legal, and built for collaboration? Commons isn’t a shortcut-it’s a standard. And the academic world is slowly catching up.

Start small. Pick one image for your next lecture. Ask your students to find one for their project. Then, think bigger. What archives are sitting in your basement or local library? They could be part of the next generation’s learning.

Can I use Wikimedia Commons images in my published research paper?

Yes, as long as the image’s license allows it. Most files on Wikimedia Commons are under public domain or Creative Commons licenses that permit academic use. Always check the license on the file’s page and include proper attribution. For example, if the license is CC BY, you must credit the creator and link to the license. Publishers often require proof of license compliance, so keep a screenshot or copy of the file’s license details.

Are all images on Wikimedia Commons copyright-free?

No. While many files are in the public domain or under permissive licenses, some carry restrictions like "non-commercial use only" or "no derivatives." Always read the license details on the file’s page. Avoid files with unclear or restrictive licenses unless you’re certain they match your use case. Never assume a file is free just because it appears on Wikipedia or Commons.

How do I properly cite a file from Wikimedia Commons?

Copy the attribution text provided on the file’s page. It usually includes the creator’s name, the title of the work, the license type, and a link to the source. For example: "Photo by John Smith, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons." If you’re using a formal citation style like APA or Chicago, adapt this into the required format. Always include the URL to the file page for verification.

Can students upload their own work to Wikimedia Commons?

Yes, and it’s encouraged. Students can upload original photos, scans of public domain documents, or illustrations they’ve created. They must confirm they own the rights and choose a license (preferably CC0 or CC BY). This teaches them about copyright, digital ethics, and contributing to public knowledge. Many educators use this as a final project-students build a portfolio of work that becomes part of a global resource.

Is Wikimedia Commons reliable for academic research?

It depends on the source. Files uploaded by institutions like NASA, the Library of Congress, or the British Museum are highly reliable. User-uploaded files vary in quality. Always verify the uploader’s credibility and check the original source if possible. Cross-reference with other archives or scholarly sources when possible. Commons is a tool-not a final authority. Use it wisely, and it’s one of the best resources available.