Over 2,000 volunteers, editors, developers, and activists from 92 countries gathered in Taipei this July for Wikimania 2025 - the biggest gathering of the Wikimedia community since the pandemic. For three days, the air buzzed with conversations about AI ethics, community safety, and how to make Wikipedia work better for people who don’t speak English. This wasn’t just another tech event. It was a living, breathing network of people who believe knowledge should be free - and that it’s worth fighting for.

What Wikimania 2025 Actually Looked Like

Forget fancy keynotes and corporate booths. Wikimania 2025 felt more like a family reunion where everyone brings something useful to the table. The main stage had no sponsors. Instead, it hosted a 16-year-old editor from Nigeria who built a bot to fix grammar errors in Yoruba Wikipedia. She didn’t have a slide deck. She had a notebook full of corrections she’d made over the past two years. The room erupted when she said, "If you can’t read Wikipedia in your language, it’s not free knowledge - it’s a library with locked doors."

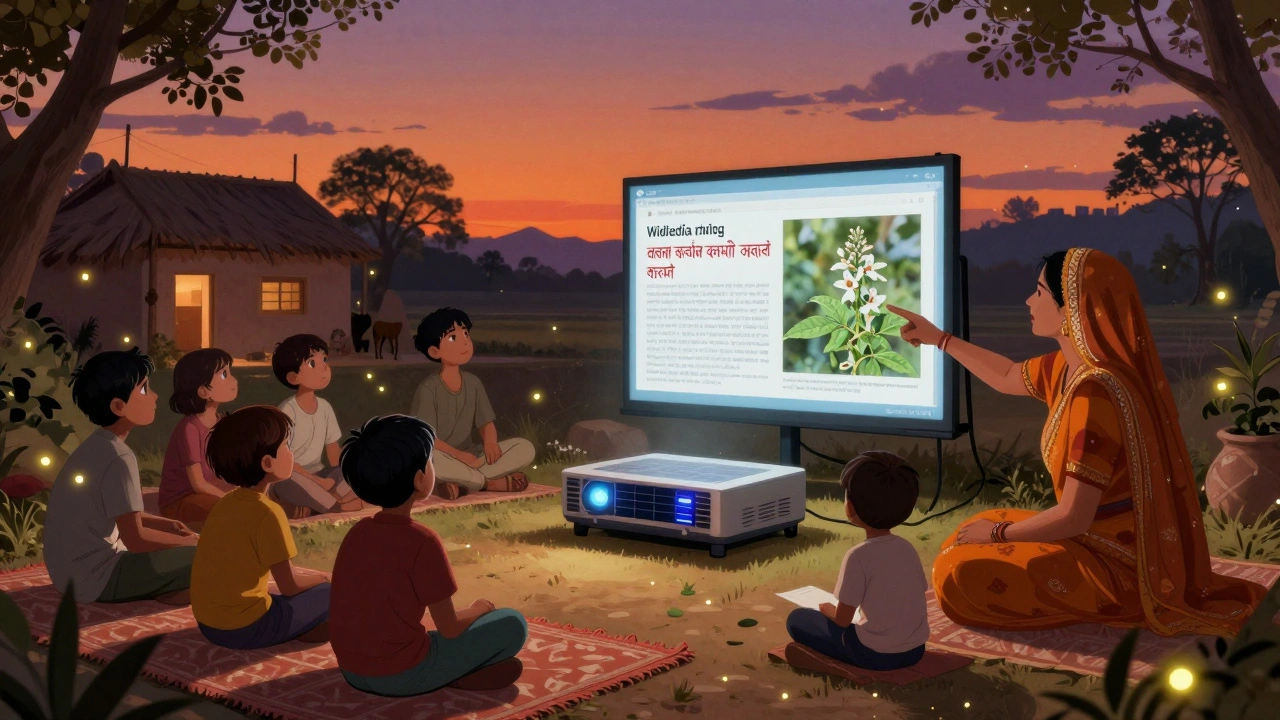

Workshops ran in parallel across 12 rooms. One session taught how to use AI tools to translate articles without losing cultural nuance. Another showed librarians in rural India how to set up offline Wikipedia servers using solar-powered Raspberry Pi units. A third group spent hours debating whether to allow AI-generated content on Commons - the media repository for Wikipedia. The vote? 78% said no. Not because they hate tech. But because they’ve seen what happens when machines rewrite history without context.

Key Announcements: What Changed

The Wikimedia Foundation made three big moves at Wikimania 2025. First, they launched the Global Knowledge Equity Fund - a $12 million initiative to support editors in low-income countries. That money isn’t going to big NGOs. It’s going directly to local groups: a collective of Indigenous women in Guatemala translating Wikipedia articles about traditional medicine, a youth group in Bangladesh creating video explainers for rural students, a network of Somali librarians digitizing oral histories.

Second, they rolled out a new moderation tool called SafeEdit. It’s not a censorship system. It’s a way for communities to flag toxic behavior before it escalates. In 2024, over 12,000 editors quit Wikipedia because of harassment. SafeEdit lets users report patterns - like repeated edits from the same IP targeting women editors - and gives local admins automated suggestions on how to respond. Early tests in the Arabic and Bengali Wikipedias cut harassment reports by 41% in six months.

Third, they announced the Wikipedia Zero project is officially dead. That’s right - after 13 years of partnering with mobile carriers to offer free access to Wikipedia without data charges, the project ended. Why? Because it didn’t fix the real problem. Free access meant nothing if the content didn’t reflect local cultures. In places like Nigeria and Indonesia, people were getting Wikipedia in English - not in their languages. The new focus? Building local content first. Access comes later.

Who Showed Up - And Who Didn’t

The attendance numbers tell a story. Brazil sent 187 editors. India sent 203. Nigeria sent 114. The United States sent 219. But here’s what’s missing: the people who don’t speak English, don’t have internet at home, or live under censorship. A delegation from North Korea didn’t show up - no surprise. But neither did a group from Eritrea. One organizer quietly told me they tried to help them get visas. They couldn’t. Not because of paperwork. Because the government blocked all travel requests from people who work on "foreign-controlled" platforms.

And yet, even those who couldn’t come were there. Over 400 people joined remotely. One woman in Sudan connected via satellite phone during a power outage. She edited Wikipedia for 90 minutes while her phone charged from a car battery. She added 17 new articles on traditional farming methods in her region. That’s the real impact of Wikimania - not in the hallways, but in the quiet corners of the world where no one’s watching.

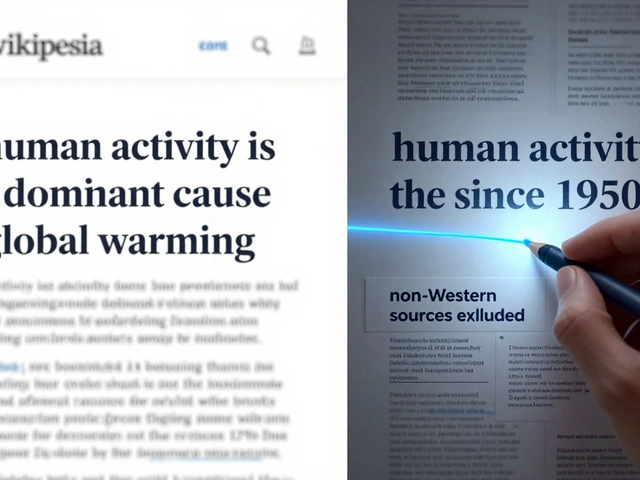

The Big Debate: AI and the Future of Wikipedia

AI came up in every conversation. Not as a tool to replace editors - but as a mirror. One panel asked: "If an AI writes a Wikipedia article about climate change, is it still knowledge?" The answer wasn’t simple. In Germany, volunteers started using AI to summarize scientific papers into plain language. The results? 32% more readers understood the content. In the Philippines, AI helped translate 15,000 articles from English into Tagalog - but only after human editors reviewed every line for cultural accuracy.

But there’s a line. A group of 40 editors from Latin America walked out of a workshop when a speaker suggested using AI to auto-generate stub articles for underrepresented topics. "We’re not here to fill space," one woman said. "We’re here to fill truth. AI doesn’t know what’s important to my grandmother’s village. Only we do."

The foundation responded by releasing a new policy: AI-generated content can appear on Wikipedia - but only if it’s clearly labeled, human-reviewed, and never used to replace community-written entries. No more "AI bots" pretending to be editors. No more hidden algorithms rewriting history. The community drew a line. And they stood by it.

What’s Next for the Wikimedia Movement

The roadmap for 2026 is clear: grow local language content, protect editors from harm, and stop pretending that access equals equity. The Global Knowledge Equity Fund will fund 200 new projects by next spring. The SafeEdit tool is being rolled out to all language editions. And the foundation is working with universities to train 5,000 new editors in Africa and Southeast Asia - not just to write articles, but to teach others how to do it.

There’s no grand announcement. No billion-dollar investment. Just a quiet commitment: if knowledge is free, then everyone deserves to shape it. Not just the ones with fast internet. Not just the ones who speak English. Everyone.

How You Can Get Involved - Right Now

You don’t need to fly to Taipei to be part of this. Here’s what you can do today:

- Find a Wikipedia article in your language that’s missing. Add one fact. Even one sentence.

- Use the "Translate" tool on Commons to help move images and documents into languages that need them.

- Join a local edit-a-thon. Check Wikimedia chapters in your country - they’re often hosted by libraries or universities.

- If you’re a teacher, ask your students to write a Wikipedia article about their family history or local landmark. It’s real research. It’s real impact.

- Donate to the Global Knowledge Equity Fund. Even $10 helps fund a translator in Nepal or a data project in Malawi.

Wikipedia isn’t a website. It’s a movement. And it’s still being written - one edit, one language, one voice at a time.

What is Wikimania?

Wikimania is the annual global conference for the Wikimedia movement - the network of volunteers who run Wikipedia and its sister projects. It’s where editors, developers, and activists meet to share ideas, solve problems, and plan the future of free knowledge. Unlike other tech conferences, there are no corporate sponsors. Everyone who speaks is a volunteer.

Was Wikimania 2025 the biggest yet?

Yes. With over 2,000 in-person attendees from 92 countries and 400 more joining remotely, it was the largest gathering in the event’s 20-year history. Attendance surpassed the 2019 conference in Stockholm, which had around 1,800 people. The growth came mostly from regions like Africa, South Asia, and Latin America - places where Wikipedia is growing fastest but has historically had less visibility.

Why did the Wikimedia Foundation end Wikipedia Zero?

Wikipedia Zero gave people free access to Wikipedia through mobile data deals - but only in English or major languages. The problem? Most people in low-income countries didn’t speak English well. So they got access to content they couldn’t understand. The foundation realized free access without relevant content wasn’t equity. They shut it down to focus on building content in local languages first - so when people get internet, they find knowledge that speaks to them.

Can AI write Wikipedia articles now?

AI can help - but only under strict rules. Any AI-generated content must be clearly labeled, reviewed by a human editor, and cannot replace articles written by the community. The goal isn’t automation. It’s augmentation. AI can summarize research or translate text, but it can’t judge what’s culturally important or historically accurate. That still needs humans.

How can I help improve Wikipedia if I’m not a tech expert?

You don’t need to code. You can fix a typo, add a citation, upload a photo, or translate a short article. Start by editing in your own language. Visit the Wikipedia Education Program page - they have simple guides for beginners. Or join a local edit-a-thon. Many libraries and schools host them. Your contribution - no matter how small - helps make knowledge more complete.

Is Wikipedia still reliable?

Yes - and it’s getting better. A 2024 study by the University of Oxford found Wikipedia’s accuracy rate for science topics is 97.8%, matching peer-reviewed journals. The key? It’s not perfect, but it’s self-correcting. Every edit is tracked. Every claim can be challenged. And every article has a talk page where editors debate the facts. That’s more transparency than most encyclopedias offer.

What This Means for the Future of Knowledge

Wikimania 2025 didn’t end with a bang. It ended with a quiet promise: knowledge isn’t something you download. It’s something you build - together. The people who showed up didn’t come for the free snacks or the swag. They came because they believe the world should have a place where anyone, anywhere, can learn what they need to know - without paying, without permission, without bias.

That’s why the real winners of Wikimania weren’t the speakers on stage. They were the 12-year-old girl in rural Kenya who added her first article about local plants. The retired teacher in Ukraine who started a weekly editing circle for seniors. The college student in Peru who translated a medical guide into Quechua so her grandmother could understand it.

Wikipedia isn’t a project. It’s a promise. And it’s still being kept - one edit at a time.