Wikipedia runs on a simple idea: anyone can edit. But when things go wrong-vandalism, harassment, edit wars, or systemic bias-the question isn’t just how to fix it. It’s who gets to fix it. That’s where the tension between the Wikimedia Foundation’s office actions and Wikipedia’s community sanctions comes alive.

What Are Office Actions?

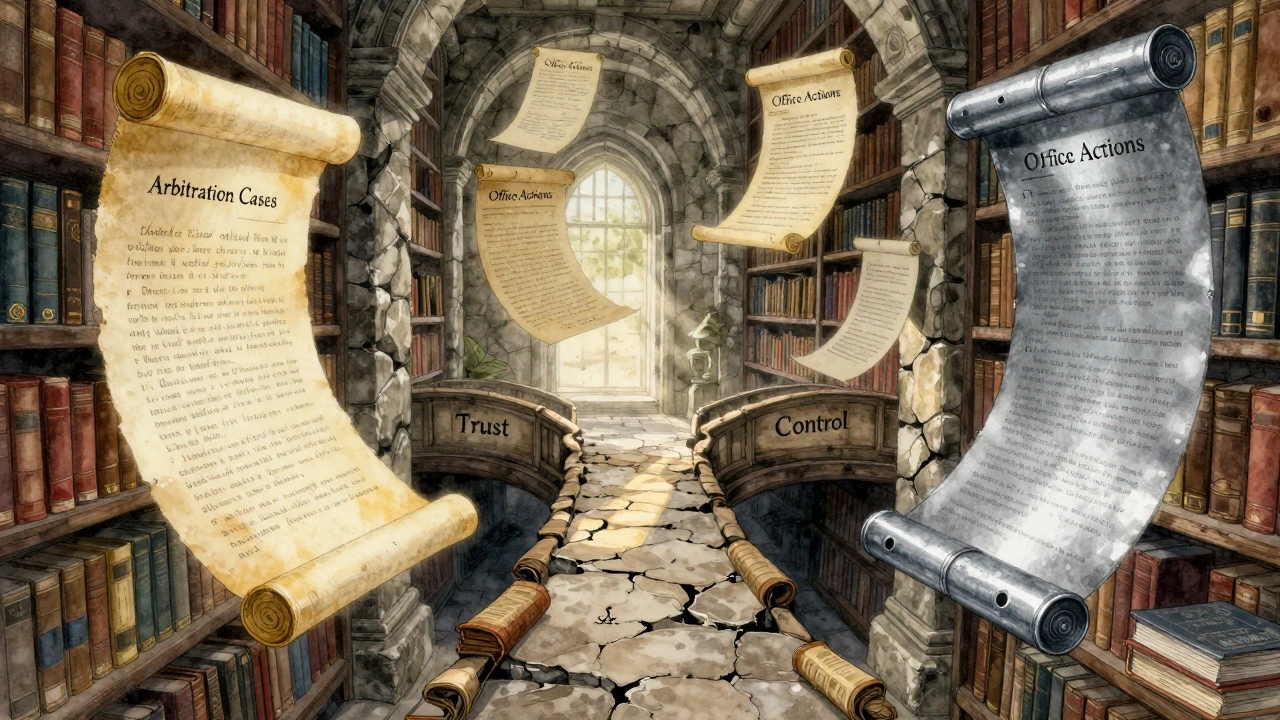

Office actions are decisions made by the Wikimedia Foundation’s staff or legal team, usually behind closed doors. These aren’t edits. They’re enforcement moves. Think bans, account restrictions, site blocks, or even removing entire pages. They happen when the community can’t or won’t act-often because the problem is too big, too legal, or too risky.

One example: in 2022, the Foundation blocked the Chinese Wikipedia entirely after persistent attempts to suppress politically sensitive content. That wasn’t a community vote. That was a legal team deciding the platform couldn’t operate under local censorship rules. Another case: in 2021, the Foundation removed the administrator rights of over 300 users across multiple language editions after a global audit found coordinated abuse of power. No community poll. No vote. Just a memo from headquarters.

These aren’t rare. Between 2020 and 2025, the Foundation issued over 1,200 office actions. Most were silent-no public explanation. A few made headlines. All of them stirred debate.

How Community Sanctions Work

Meanwhile, Wikipedia’s volunteer editors have their own system. It’s messy. It’s slow. But it’s democratic. Community sanctions include warnings, probation, topic bans, arbitration, and page protections. All of these are decided through discussion, voting, and consensus on talk pages.

Take the case of a longtime editor on the English Wikipedia who repeatedly inserted false claims about a public figure. The community didn’t just revert edits. They opened a formal arbitration case. Over six weeks, 47 editors reviewed evidence, wrote opinions, and voted. The result? A two-year topic ban on that person’s edits related to that figure. The decision was published. The reasoning was public. Everyone could see how it happened.

That’s the beauty-and the flaw-of community sanctions. Transparency. Participation. Accountability. But also: burnout, bias, and endless debate. A 2023 study of 500 arbitration cases found that 68% took longer than 90 days to resolve. Half of those involved editors who quit afterward, saying the process was too draining.

When Office Actions Step In

Office actions don’t replace community sanctions. They step in when the community breaks down.

Imagine a group of editors systematically harassing a newcomer. They leave threatening messages. They dox personal details. They coordinate to block the user from editing. The community tries to respond. But the harassers are well-organized. They’ve created sock puppets. They’ve flooded the talk pages. The community is exhausted. The victim leaves.

That’s when the Foundation acts. They don’t wait for consensus. They look at server logs, IP patterns, and user reports. Then they block the accounts. They freeze the edits. Sometimes they even contact law enforcement. This isn’t about opinion. It’s about safety.

Another trigger: legal threats. If a Wikipedia page risks violating copyright, defamation, or privacy laws in multiple countries, the Foundation can’t rely on editors to fix it. They have lawyers. They have compliance teams. They act. Fast.

Why Community Sanctions Still Matter

Office actions keep Wikipedia running. But community sanctions keep it honest.

Wikipedia’s credibility doesn’t come from its servers. It comes from its editors. Millions of them. Volunteers. Teachers. Retirees. Students. They’re the ones who spot bias, correct misinformation, and debate what counts as reliable sourcing.

When the Foundation bans an editor for “disruptive behavior,” the community often asks: why? Was it a genuine violation? Or did someone just disagree with their edits? In 2024, a high-profile case on the German Wikipedia saw the Foundation ban an editor who had been correcting false claims about climate change. The community pushed back. They dug into the edit history. They found the editor had been correct 94% of the time. The Foundation reversed the ban two weeks later.

That’s the check. The community doesn’t always win. But it often forces the Foundation to explain itself. And that’s how Wikipedia stays grounded.

The Real Conflict: Power vs. Participation

The tension between office actions and community sanctions isn’t about who’s right. It’s about control.

The Foundation sees itself as the guardian of Wikipedia’s legal and technical survival. They fund the servers. They hire the engineers. They answer to donors and regulators. They can’t afford to let Wikipedia become a battleground for every dispute.

The community sees itself as the soul of Wikipedia. They built it. They maintain it. They know its quirks, its history, its unwritten rules. They don’t trust outsiders to understand how it works.

This isn’t new. In 2013, the Foundation introduced the “Arbitration Committee Oversight Policy,” giving staff the power to review arbitration decisions. It was meant to prevent abuse. But many editors saw it as a power grab. Over 1,500 signed a petition. Some stopped editing.

Since then, the Foundation has tried to walk a line. They’ve created public logs for office actions. They’ve invited community reps to internal meetings. They’ve published annual transparency reports. But the trust gap remains.

What’s the Balance?

There’s no perfect answer. But here’s what works:

- Office actions should be rare, documented, and reversible.

- Community sanctions should be fast, fair, and transparent.

- When the Foundation acts, it should explain why the community couldn’t.

- When the community acts, it should be ready to handle the fallout.

The most successful Wikipedia pages aren’t the ones with the most edits. They’re the ones with the most trust. And trust doesn’t come from a policy document. It comes from knowing that the system-no matter how flawed-is still listening.

What Happens When the System Breaks?

Look at the French Wikipedia in 2023. A dispute over a biography of a politician spiraled into a months-long edit war. The community couldn’t agree. The Foundation stepped in with a site-wide restriction on editing the page. But they didn’t just lock it. They opened a public consultation. They invited historians, journalists, and neutral editors to review sources. They published the findings. Then they lifted the restriction.

That’s the model. Not top-down control. Not bottom-up chaos. But a bridge between the two.

Wikipedia’s future won’t be decided by lawyers or by editors alone. It’ll be decided by how well those two sides learn to work together.

Can the Wikimedia Foundation ban editors without community input?

Yes. The Wikimedia Foundation has the legal authority to restrict or ban any user account at any time, regardless of community opinion. This power is used when actions violate laws, threaten safety, or involve coordinated abuse that the community cannot resolve. Examples include doxxing, harassment campaigns, or legal violations. While the Foundation usually consults community feedback, it is not required to do so.

Why do some editors distrust office actions?

Many editors distrust office actions because they’re often opaque, inconsistent, and seem to override years of community consensus. There’s a fear that staff, who aren’t editors themselves, lack the cultural understanding of Wikipedia’s norms. Past incidents-like the removal of trusted administrators without clear explanation-have deepened this mistrust. Transparency has improved, but the perception of top-down control remains.

Do community sanctions ever fail?

Yes. Community sanctions often fail when disputes become too personal, too politicized, or too complex. In cases involving systemic bias, organized vandalism, or high-profile figures, discussions can become endless, hostile, or manipulated. Studies show that over 40% of arbitration cases on major language editions stall for more than 6 months. In those cases, the community effectively freezes, and the problem remains unresolved until the Foundation intervenes.

Are office actions more common now than in the past?

Yes. Between 2015 and 2025, office actions increased by over 300%. This rise correlates with growing legal pressures, geopolitical censorship, and increased harassment of editors. The Foundation now has a dedicated Trust & Safety team with over 50 staff members, compared to just 3 in 2015. While community size has plateaued, the number of serious violations has surged, forcing more direct intervention.

Can a banned editor appeal an office action?

Appeals are possible but difficult. The Foundation accepts formal appeals through its legal review process, but only in limited cases-usually involving misapplication of policy or procedural errors. Appeals are not guaranteed to be reviewed. Most are denied without public explanation. In contrast, community sanctions can be appealed through talk page discussions, arbitration, or community votes, which are open and transparent.